Figure 1: Triple protostar system L1448 IRS3B, showing a central binary pair of protostars (IRS3B-a & IRS3B-b, with a combined mass of ∼1 M☉), orbited by a less-massive but much-brighter companion protostar (IRS3B-c, with a mass of ∼0.085 M☉) in a circumbinary orbit.

Figure 1: Triple protostar system L1448 IRS3B, showing a central binary pair of protostars (IRS3B-a & IRS3B-b, with a combined mass of ∼1 M☉), orbited by a less-massive but much-brighter companion protostar (IRS3B-c, with a mass of ∼0.085 M☉) in a circumbinary orbit.

An alternative ideology, presented here, suggests that the luminosity difference results from age difference, in a stellar system that turned itself inside out by a flip-flop mechanism, designated, symmetrical flip-flop fragmentation (symmetrical FFF). A high angular momentum accretion disk in the form of a dynamical bar-mode instability underwent disk fragmentation to form a twin pair of disk-fragmentation objects in orbit around the diminutive but more evolved protostellar core at the center of rotation. Then, equipartition of kinetic energy during orbital interplay gradually flip-flopped the former prostellar core into a circumbinary orbit around the much-more-massive but less-evolved twin disk-fragmentation objects, forming the observed hierarchical trinary protostar system.

Image Credit: Bill Saxton, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO), NRAO/AUI/NSF – Publication: John Tobin (Univ. Oklahoma/Leiden) et al.

Abstract

¶

¶ This alternative conceptual study proposes several alternative mechanisms for catastrophically projecting mass inward in rotating, gravitationally bound astrophysical systems, resulting in alternative planetary and stellar formation mechanisms that accelerate the increase in entropy.

¶ A counterintuitive study (Tychoniec et al., 2018) found decreasing accretion disk mass with protostellar evolution. Disk dust mass was measured to decrease from 248 M⊕ in Class 0 protostars, to 96 M⊕ in Class I protostars, to 5–15 M⊕ in Class II protostars. This suggests the possibility of an early crossover point, where the disk mass could be (much) greater than the central protostar mass, especially if this discovery extends backward across the presteller-protostellar boundary to still younger prestellar systems with still smaller prestellar central cores. In a hypothetical system where the disk mass greatly exceeds the central core mass, the disk would have inertial dominance, such that the diminutive core would be unable to damp down disk inhomogeneities from amplifying into global disk fragmentation. And a stellar-mass disk fragmentation around a planetary-mass prestellar/protostellar central core would cause an inertial flip-flop, injecting the former core into a planetary orbit around the nascent disk-fragmentation object in a mechanism designated, ‘asymmetrical flip-flop fragmentation (asymmetrical FFF), making giant planets the older progenitors of their host stars.

¶ The bimodal populations of hot and cold Jupiters are separated by a 10–100 d orbital-period valley. This study suggests that hot Jupiters result from disk fragmentation of protostellar disks, while cold Jupiters result from disk fragmentation of more distant pseudodisks.

¶ In a system where high specific angular momentum distorts a protostellar disk into a dynamical bar-mode instability, disk fragmentation may trifurcate the triaxial bar, forming a twin pair of disk-fragmentation objects in orbit around the diminutive protostellar central core at the center of rotation in a process designated, ‘symmetrical FFF’. Symmetrical FFF forms unstable ternary systems that evolve through orbital interplay into stable hierarchical systems, most typically composed of the former diminutive protostellar core (companion) in a circumbinary orbit around the much-more-massive twin disk-fragmentation objects (binary stellar pair). The trinary Alpha Centauri system is a typical ternary star system formed by symmetrical FFF, and this study suggests that our own solar system also formed by symmetrical FFF, initially creating twin disk-fragmentation objects (that became our former Binary-Sun) around a brown-dwarf-mass former protostellar core.

¶ Asymmetrical FFF presumably forms giant planets, from mini-Neptunes through super-Jupiters and possibly up to low mass brown dwarfs, while symmetrical FFF tends to form more-massive objects, like brown dwarfs and red dwarf companion stars.

¶ This study suggests a third and very rare mechanism for planet formation in symmetrical FFF systems, in which the protostellar core is induced to spin-up during orbital interplay to the point of centrifugal fragmentation into 3 components by a well-constrained process designated ‘trifurcation’. During orbital interplay following symmetrical FFF, orbital close encounters between a diminutive protostellar core and it’s much-more-massive twin disk-fragmentation objects (nascent stars) results in equipartition of kinetic energy, which transfers kinetic energy and angular momentum from the more massive twin components to the diminutive protostellar core. This study suggests that equipartition of kinetic energy also extends to rotation, causing the core to spin up, possibly to the point of centrifugal fragmentation. Progressive spin up causes flattening of the core into an oblate sphere, followed by distortion into a triaxial Jacobi ellipsoid and then into a bar-mode instability. The centrifugal failure mode of a bar-mode instability is hypothesized here to be gravitational fragmentation into 3 components, hence trifurcation, which is analogous to the process for symmetrical FFF. The self-gravity of a bar-mode instability causes fragmentation, wherein the ends of the central bar gravitationally pinch off into independent Roche spheres, forming a twin-pair of gravitationally bound objects in orbit around the diminutive ‘residual core’, remaining at the center of rotation. This newly trifurcated system is a miniature version of the original symmetrical FFF system, which is similarly dynamically unstable. Thus, first-generation trifurcation promotes second-generation trifurcation, and etc., potentially forming multiple generations of twin binary pairs of objects in diminishing sizes like Russian nesting dolls. This study suggests that our solar system underwent symmetrical FFF, followed by 4 generations of trifurcation, creating a former Binary-Companion to the Sun with super-Jupiter-mass binary components in the 1st generation trifurcation, followed by 3 subsequent trifurcation generations as follows:

1) Symmetrical FFF―forming Binary-Sun (twin disk fragmentation objects) + Brown Dwarf* (protostellar core)

2) 1st-generation trifurcation―forming Binary-Companion + SUPER-Jupiter* (residual core)

3) 2nd-gen. trifurcation―forming Jupiter-Saturn + SUPER-Neptune* (residual core)

4) 3rd-gen. trifurcation―forming Uranus-Neptune + SUPER-Earth* (residual core)

5) 4th-gen. trifurcation―forming Venus-Earth + Mercury (residual core)

This accounting leaves out Mars, which presumably formed by ‘hybrid accretion’ like super-Earths, with ‘hybrid’ indicating hierarchical accretion of planetesimals formed by streaming instability.

¶ The trifurcated binary pairs from the 4 trifurcation generations extracted binary-binary resonant energy from former Binary-Sun, causing the binary pairs to spiral out from the gravitational wells of their ‘parent’ and ‘grandparent’ systems until they were captured by former Binary-Sun into heliocentric orbits. And the sibling binary pairs continued to spiral out from their binary barycenters until they separated to form solitary planets, except for Binary-Companion, which remained a binary pair. Ultimately, Binary-Sun spiraled in and merged at 4,567 Ma, forming a luminous red nova (LRN), with stellar-merger nucleosynthesis creating some of the short-lived radionuclides of our early solar system, notably Al-26 and Ca-41. And the stellar merger created the ‘solar-merger debris disk’, which spawned the asteroid belt in situ by streaming instability.

¶ Former Binary-Companion presumably orbited between Saturn and Uranus for nearly 4 billion years. Secular perturbation by the Sun caused the super-Jupiter-mass binary components to slowly spiral in, transferring their binary energy to progressively increasing the period of the heliocentric orbit. This progressive increase in heliocentric period caused its 4:1 mean motion resonance to progressively sweep outward through the Kuiper belt, perturbing Kuiper belt objects (KBOs), causing the late heavy bombardment (LHB) of the inner solar system. Ultimately, the binary components merged at 639 Ma in an asymmetrical merger explosion that gave newly merged Companion escape velocity from the Sun. And the resulting ‘Companion-merger debris disk’ spawned the young (639 Ma) cold-classical KBOs and fogged the solar system, causing the Marinoan glaciation on Earth.

* Note, unorthodox capitalization indicates unorthodox definitions. ‘Brown Dwarf’ is the name of the original protostellar core of the solar system, and ‘SUPER-Jupiter’, ‘SUPER-Neptune’ and ‘SUPER-Earth’ are the names for the transient residual cores formed in the first three trifurcation generations.

………………..

¶

Table of Contents

¶

1. Introduction

2. Hybrid accretion planets and moons

3. Flip-Flop Fragmentation (FFF)

4. Trifurcation by centrifugal fragmentation

5. Trifurcation moons

6. Former Binary-Companion

7. Protostellar disk and 3 debris disks

8. Venusian cataclysm

9. Solar system summary

10. The predictive and explanatory power of FFF-trifurcation ideology

References

¶

1. Introduction

¶

¶ The alternative conceptual astrophysics of this study is largely premised on several catastrophic mechanisms for the inward projection of mass in rotationally supported systems, with at least 2 mechanisms being entirely novel.

¶ The first novel mechanism is an inside-out formation mechanism for stellar systems with gas-giant planets, accompanied by a flip-flop, in which gas-giant planets originally formed as the central prestellar/protostellar objects at the center of rotation, followed by an inertial flip-flop due to a stellar-mass disk fragmentation of the surrounding protostellar disk. Disk fragmentation that breaks the radial symmetry of a stellar-mass protostellar disk around a planetary-mass prestellar/protostellar central object results in an inertial flip-flop, injecting the former core into a planetary satellite orbit around the nascent stellar-mass disk fragmentation object. This is an even more catastrophic mechanism than giant planet formation by disk instability, which is an important alternative hypothesis to the standard core accretion model.

¶ The second novel mechanism is the Russian nesting doll clockwork mechanism for the formation of the 3-sets of twin planets in our highly unusual solar system, namely Jupiter-Saturn, Uranus-Neptune and Venus-Earth + Mercury. This mechanism suggests that the equipartition of kinetic energy during orbital interplay that resolves stellar systems born nonhierarchical into stable hierarchical systems has a rotational component, tending to cause a diminutive ternary ‘companion’ to spin-up, while being ‘evaporated’ into a circumbinary orbit. In flat well-aligned stellar systems, this rotational spin-up may induce centrifugal fragmentation in a highly regimented fashion into 3 components, creating a massive twin binary pair in orbit around a diminutive residual core remaining at the center of rotation in a centrifugal-fragmentation mechanism designated ‘trifurcation’. Trifurcation creates a local decrease in entropy in the trifurcated companion, but results in an overall increase in entropy by projecting mass inward in the binary pair that induced the spin-up fragmentation during orbital interplay. This study suggests that our solar system originally formed as a ternary system like Alpha Centauri, but with 4 generations of trifurcation that created sufficient binary-binary resonance chasing to cause our former Binary-Sun to spiral in and merge at 4,567 Ma.

¶ Academia seems to be warming to a catastrophic origin of small solar system bodies (SSSBs) by gravitational collapse, by dust enhancement by streaming instability. Contact binaries and wide binary Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) of comparable mass may best be explained by gravitational collapse (Nesvorný et al., 2010). Similarly, the formation of binary and ternary star systems with twin components of comparable mass in close-binary orbits, like the Alpha Centauri star system, may be best explained by the catastrophic mechanism of disk fragmentation, as in the triple protostar system L1448 IRS3B (Tobin et al. 2016).

¶ Strategically combining these and other mechanisms, as laid out in this study, conceptually unifies many otherwise ad hoc solar system phenomena in a far-more falsifiable clockwork model than the standard clockwork models.

Hybrid accretion planets and moons § 2:

¶ Chains of super-Earths and chains of well-ordered moons around giant planets are suggested here to have formed by ‘hybrid accretion’, which is a hybrid mechanism consisting hierarchical accretion of planetesimals formed by streaming instability.

¶ Planetesimals that form by streaming instability at pressure bumps, particularly at the truncated inner edge of protoplanetary disks, may accrete to form planets, which may clear their orbits when attaining the nominal mass of a super-Earth.

¶ And super-Earth formed at the inner edge of a protoplanetary disk that clears its orbit pushes the inner edge of the protoplanetary disk outward, which may spawn a second generation of planetesimals by streaming instability against its strongest outer resonances, which may accrete to form a second super-Earth. In this way, chains of super-Earths and chains of moons around giant planets may form sequentially from the inside out by hybrid accretion.

Flip-Flop Fragmentation (FFF) § 3:

Terminology:

– A ‘dark core’ refers to a dense, cold region within a molecular cloud that may or may not be in a condition of freefall, which is dark because of its high opacity due to high density.

– A ‘protostar’ or central ‘prestellar object’ will be defined here to refer specifically to the central spherical object (nascent star) inside the ‘accretion disk’, and when the prestellar/protostellar phase is indeterminate, the central spherical object will be termed a ‘prestellar/protostellar central core’ or merely ‘central core’, and the term ‘former core’ refers to a central core that has been displaced by a flip-flop mechanism. ‘Accretion disk’ and ‘protostellar disk’ may be used interchangeably in this study to describe the early protoplanetary disk during the prestellar/early protostellar phase, generally avoiding the term ‘protoplanetary disk’, which has planetary connotations.

– ‘Disk instability’ is an alternative standard model hypothesis to core accretion for form forming gas giant exoplanets by a local mechanism, but this study suggests that disk instability necessitates a global mechanism that necessarily results in disk-instability objects that are much-more massive than their central prestellar/protostellar central cores. To distinguish classical disk instability, which is a local phenomenon, from the global form, suggested here, the global form of disk instability will be designated ‘disk fragmentation’, forming ‘disk-fragmentation objects’. Generally speaking, ‘disk fragmentation’ may be used interchangeably with ‘asymmetrical FFF’, but more precisely, disk fragmentation encompasses the entire process of global disk fragmentation, whereas asymmetrical FFF focuses on the resulting flip-flop between the resulting disk-fragmentation object and the former core.

Asymmetrical flip-flop fragmentation (asymmetrical FFF):

¶ A counterintuitive recent discovery finds that protoplanetary disks have their highest mass at earliest times, promoting disk fragmentation. “We find that the compact (< 1″) dust emission is lower for Class I sources (median dust mass 96 M⊕) relative to Class 0 (248 M⊕), but several times higher than in Class II (5-15 M⊕). If this compact dust emission is tracing primarily the embedded disk, as is likely for many sources, this result provides evidence for decreasing disk masses with protostellar evolution, with sufficient mass for forming giant planet cores primarily at early times.” (Tychoniec et al. 2018)

¶ “The compact components around the Class 0 protostars could be the precursors to these Keplerian disks. However, it is unlikely that such massive rotationally supported disks could be stably supported given the expected low stellar mass for the Class 0 protostars: they should be prone to fragmentation”. (Li et al. 2014)

¶ If protoplanetary disks are most massive at earliest times, then the dynamic stability of early protostellar and possibly prestellar systems may be called into question. Toomre’s stability criterion governs local ‘disk instability’, but when a disk is much-more massive than its diminutive central core, then the disk has inertial dominance of the system, such that positive feedback may result in runaway global disk fragmentation, affecting the entire disk. And a resulting disk-fragmentation object will necessarily be much-more massive than its diminutive central core, resulting in an inertial flip-flop that injects the former core into a planetary satellite orbit around the disk-fragmentation object (nascent star), in a process designated, ‘asymmetrical FFF’.

¶ The bimodal populations of hot and cold Jupiters, separated by a 10–100 d orbital-period valley, appear to telegraph separate origins for hot and cold Jupiters, where the standard model of planetary migration requires an unlikely all-or-nothing migration mechanism, resulting in a ‘discreteness problem’ for the standard model. Alternatively, if hot Jupiters result from disk fragmentation of protostellar disks (accretion disks) and cold Jupiters result from disk fragmentation of magnetically-controlled pseudodisks, then the discreteness problem is avoided.

¶ Asymmetrical FFF predominantly forms planetary-mass objects, from mini-Neptunes up to super-Jupiters and possibly up to low-mass brown dwarfs.

Symmetrical FFF:

¶ When a collapsing dark core has particularly high specific angular momentum, or the infalling dust and gas overwhelms the nebular magnetic field which projects angular momentum outward, the infalling dust and gas may form a bilaterally-symmetrical dynamical bar-mode instability, rather than a radially-symmetrical accretion disk. If such a dynamical bar-mode instability reaches sufficient mass and specific angular momentum for self-gravity to fragment the bar, this study suggests that the outcome will be trifurcation, fragmenting the bar into 3 components, consisting of a massive twin pair from the ends of the bar and a diminutive central core at the center of rotation. This creates a nonhierarchical trinary orbital system, composed of a twin pair in orbit around a diminutive core in a process designated, ‘symmetrical FFF’. And similar to asymmetrical FFF, symmetrical FFF is posited to involve global disk fragmentation.

¶ Symmetrical FFF creates an unstable, nonhierarchical trinary system, which evolves by orbital interplay into a stable hierarchical system, most typically injecting the former core into a circumbinary orbit around the twin components. Equipartition of kinetic energy in orbital close encounters during orbital interplay tends to transfer orbital energy and angular momentum from the more-massive twin components to the less-massive former core, which gradually ‘evaporates’ the diminutive former core into a circumbinary orbit as a ‘companion’ of the binary pair, creating a stable hierarchical system. The spiral-in of the twin components typically forms a binary pair, but may cause the binary pair to merge in a luminous red nova, converting the trinary system into a binary system, with the companion as the diminutive partner.

¶ The mass of former cores in symmetrical FFF may overlap the upper-mass range of former cores in asymmetrical FFF, and extend it to high-mass brown dwarfs and main-sequence stars. The massive twin components are generally main-sequence stars, but may be brown dwarfs and possibly as small as super-Jupiter-mass objects, possibly explaining binary super-Jupiter-mass objects, recently found by JWSP in the Trapezium Cluster of the Orion Nebula (Pearson and McCaughrean, 2023).

Trifurcation § 4:

¶ The 3 sets of twin planets in our highly-unusual solar system (Jupiter-Saturn, Uranus-Neptune and Venus-Earth + Mercury) are hypothesized here to have formed like Russian nesting dolls in successive generations of a dynamic mechanism designated, ‘trifurcation’. This study suggests a symmetrical FFF origin for our solar system, with a brown-dwarf-mass protostellar core and a twin pair of disk instability objects that became our former Binary-Sun. Then this symmetrical FFF trio initiated a multi-generational trifurcation process.

¶ In orbital close encounters between objects with a large mass disparity, the diminutive object receives a kinetic energy kick in a process known as equipartition of kinetic energy, which is the principle of gravitational assist used by interplanetary spacecraft. Equipartition of kinetic energy converts chaotic non-hierarchical systems into circumbinary hierarchical systems through orbital interplay. The principle of trifurcation suggests that that our former brown dwarf protostellar core received a rotational kick in addition to an orbital kick from equipartition of kinetic energy, causing a rotational spin up from orbital close encounters with the much-more-massive former Binary-Sun components. Centrifugal fragmentation from rotational spin up is the principle of trifurcation, wherein centrifugal fragmentation occurs by way of a bar-mode instability in which the bar trifurcates into a twin binary pair in orbit around the diminutive ‘residual core’. And because newly-trifurcated systems are mini versions of symmetrical FFF systems, they themselves are subject to next-generation trifurcation.

¶ In this manner, our former symmetrical FFF system presumably underwent 4 generations of trifurcation, forming

– 1st-gen: ‘Binary-Companion’ + ‘SUPER-Jupiter’ (residual core)

– 2nd-gen: Jupiter & Saturn + ‘SUPER-Neptune’ (residual core)

– 3rd-gen: Uranus & Neptune + ‘SUPER-Earth’ (residual core)

– 4th-gen: Venus & Earth + Mercury (residual core)

¶ The resulting ‘trifurcation debris disk’ spawned the hot classical Kuiper belt objects (KBOs). And binary-binary resonances with former Binary-Sun caused Jupiter-Saturn, Uranus-Neptune and Venus-Earth to spiral out and separate, leaving only former Binary-Sun and former Binary-Companion as binary subsystems. Then former Binary-Sun spiraled in and merged at 4,567 Ma in a luminous red nova, creating the ‘solar-merger debris disk’ that spawned the asteroids, and former Binary-Companion spiraled and merged at 639 Ma in an asymmetrical merger explosion that gave the newly merged Companion escape velocity from the Sun and forming the ‘Companion-merger debris disk’ that spawned the cold-classical KBOs.

Trifurcation moons and the Venusian cataclysm § 4, § 5:

¶ Trifurcation may be slightly more complex than the simplistic mechanism outlined above, which is expressed in a more complete form as the ‘trifurcation+2’ mechanism. In computer simulations, bar-mode instabilities have tails trailing from the twin ends of the central bar, which are suggested here to self-gravitate and form a twin pair of moons. ‘Trifurcation moons’ are stillborn, in a sense, being born without kinetic energy or angular momentum with respect to their respective twin planetary components, to which they are gravitationally bound. But due to the extreme dynamics of the trifurcation+2 subsystem within the greater system that induced trifurcation, the moons quickly acquire angular momentum with respect to the planets to which they are gravitationally bound, necessarily injecting one moon into a prograde orbit and its twin moon into a retrograde orbit. Thus, in the 4th generation trifurcation, Earth acquired its oversized trifurcation Moon (Luna) in a prograde orbit, and Venus acquired an oversized trifurcation moon in a retrograde orbit.

¶ This is the present and former list of trifurcation moons:

– Neptune with retrograde Triton

– Uranus with a former prograde moon

– Saturn with prograde Titan

– Jupiter with a former retrograde moon

– Earth with prograde Luna

-Venus with a former retrograde moon

¶ Jupiter’s former retrograde moon may have spiraled in and merged with the planet at 4,562 Ma, forming enstatite chondrites that lie on the terrestrial fractionation line. Uranus presumably lost all its original moons, including its prograde trifurcation moon, in orbital close encounters with former Binary-Companion, and later spawned a young set of hybrid-accretion moons from the 639 Ma Companion-merger debris disk. And finally, Venus’ former retrograde trifurcation moon spiraled in and merged with the planet, presumably at 579 Ma, causing the ‘Venusian cataclysm’ which completely resurfaced the planet and caused Venus’ slight retrograde rotation, as well as presumably causing Gaskiers glaciation on Earth.

Star formation stages:

¶ 1. Starless core: May be a transient phase or may progress to Jeans instability.

¶ 2. Prestellar core: The initial collapse phase ends when the core becomes optically thick, forming a pressure-supported first hydrostatic core (FHSC). The FHSC phase ends when molecular hydrogen endothermically dissociates into atomic hydrogen around 2000 K, causing a brief second collapse. The FHSC marks the end of the prestellar phase.

¶ 3. Protostar (Class 0, I, II, III): Begins with the collapse of the FHSC, designated the ‘second collapse’, which creates a second hydrostatic core (SHSC).

¶ 4. Pre-main-sequence star: A T Tauri, FU Orionis, or larger pre-main-sequence star powered by gravitational contraction.

¶ 5. Main-sequence star: Powered by hydrogen fusion.

¶ “Starless cores are possibly transient concentrations of molecular gas and dust without embedded young stellar objects (YSOs), typically observed in tracers such as C18O (e.g. Onishi et al. 1998), NH3 (e.g. Jijina, Myers, & Adams 1999), or dust extinction (e.g. Alves et al. 2007), and which do not show evidence of infall. Prestellar cores are also starless (M⋆ = 0) but represent a somewhat denser and more centrally-concentrated population of cores which are self-gravitating, hence unlikely to be transient.” (André et al. 2008)

¶ In Jeans instability, the cloud collapses at an approximately free-fall rate nearly isothermally at about 10 K until the center become optically thick at ~10-13 g/cm3 after 105 yr (Larson 1969). When the center becomes optically thick, the temperature begins to rise, forming a FHSC. “Numerical results for a typical case … show that the radius and mass of the first core are ~5 AU and ~0.05 M☉, respectively. These values are independent both of the mass of the parent cloud core and of the initial density profile.” When the temperature reaches about 2000 K, the hydrogen begins to dissociate endothermically, forming the second core, the birth of a protostar. The protostar grows in mass by accreting the infalling material from the circumstellar envelope, while the protostar keeps its radius at ~4 R☉ during the main accretion phase. (Masunaga et al. 1998)

¶ Vaytet et al. (2013) finds a variable first core, but a standard size for the second core. “The size of the first core was found to vary somewhat in the different simulations (more unstable clouds form smaller first cores) while the size, mass, and temperature of the second cores are independent of initial cloud mass, size, and temperature.

Conclusions. Our simulations support the idea of a standard (universal) initial second core size of ~3×10-3 AU and mass ~1.4×10-3 M☉.”

(Vaytet et al. 2013)

¶ A relatively consistent modest mass for the first collapse, the FHSC, and the early SHSC could allow for an oversized protellar disk to have inertial dominance of the system, promoting disk fragmentation.

FHSC:

¶ The development of a bar mode and spiral structure is expected for rapidly rotating polytropic-like structures (e.g. Durisen et al. 1986). Such instabilities occur when the ratio of the rotational energy to the magnitude of the gravitational potential energy of the first core exceeds β = 0.274. Bate was also the first to point out that because a rapidly rotating first core develops into a disc before the stellar core forms, the disc forms before the star. Rather than hydrostatic cores, such structures are better described as ‘pre-stellar discs’.

¶ Without rotation (β = 0), the first core has an initial mass of ≈5 MJ and a radius of ≈5 au (in agreement with Larson 1969). However, with higher initial rotation rates of the molecular cloud core, the first cores become progressively more oblate. For example, with β = 0.005 using radiation hydrodynamics, before the onset of dynamical instability, the first core has a radius of ≈20 au and a major-to-minor-axis ratio of ≈4:1. With β = 0.01, the first core has a radius of ≈30 au and a major-to-minor-axis ratio of ≈6:1. Thus, for the higher rotation rates, the first core is actually a pre-stellar disc, without a central object. As pointed out by Bate (1998), Machida et al. (2010) and Bate (2010), the disc actually forms before the star. For the very highest rotation rates (β = 0.04), the first core actually takes the form of a torus or ring in which the central density is lower than the maximum density.

¶ In each of the β = 0.001–0.005 cases, the first core begins as an axisymmetric flattened pre-stellar disc, but after several rotations, it develops a bar mode. The ends of the bar subsequently lag behind and the bar winds up to produce a spiral structure. Spiral structure removes angular momentum from the inner parts of the first core via gravitational torques (Bate 1998).

(Matthew R. Bate, 2011)

¶ “Class 0 objects are the youngest accreting protostars observed right after point mass formation, when most of the mass of the system is still in the surrounding dense core/envelope (Andre et al. 2000).”

(Chen et al. 2012)

¶ “Enoch et al. (2009a) discovered a massive circumstellar disk of ∼1 M☉ comparable to a central protostar around a Class 0 object, indicating that (1) the disk already exists in the main accretion phase and (2) the disk mass is significantly larger than the theoretical

prediction.” (Machida et al. 2011)

Evidence for Kuiper belt objects (KBOs) formed by gravitational/streaming instability:

¶ “The 100 km class binary KBOs identified so far are widely separated and their components are similar in size. These properties defy standard ideas about processes of binary formation involving collisional and rotational disruption, debris re-accretion, and tidal evolution of satellite orbits

(Stevenson et al. 1986).” “The observed color distribution of binary KBOs can be easily understood if KBOs formed by GI [gravitational instability].” “We envision a situation in which the excess of angular momentum in a gravitationally collapsing swarm prevents formation of a solitary object. Instead, a binary with large specific angular momentum forms from local solids, implying identical composition (and colors) of the binary components.”

(Nesvorny et al. 2010)

………………..

2. Hybrid accretion planets and moons

¶

¶ ‘Hybrid accretion’ is a working hypothesis for the formation of cascades or chains of well-behaved super-Earths in stellar systems and similar groupings of well-behaved moons around giant planets. This alternative planet formation mechanism combines the formation of planetesimals by streaming instability with the hierarchical accretion of these planetesimals into super-Earths or moons, hence the term “hybrid” accretion.

¶ This hybrid mechanism for planet formation was first proposed for the formation of gas giant planets by Thayne Curie (2005), but is proposed here for the formation cascades of super-Earths and similar cascades of moons.

¶ In protostellar disks, gas rotates at a sub-Keplerian rate due to pressure support, while dust particles, which do not experience pressure forces, must orbit at the Keplerian rate to maintain a stable orbit. The difference in rotational speeds creates a drag force on the dust, causing it to lose angular momentum and spiral inward. This process can lead to the accumulation of dust at regions of higher pressure, known as ‘pressure bumps.’ If the dust density at these bumps becomes high enough, it may trigger the streaming instability—a type of gravitational instability that can enhance dust clumping and potentially lead to planetesimal formation.

¶ This study suggests the sequential inside-out formation of hybrid-accretion cascades, where the innermost hybrid accretion object presumably forms at a pressure bump that constitutes the inner edge of the accretion disk, which is controlled by the magnetospheric radius, where the pressure from the star’s magnetic field balances the dynamic pressure of the accreting material in the disk. At the pressure bump constituting the inner edge of the accretion disk, streaming instability may form zillions of ~ 100 km planetesimals, which merge by hierarchical accretion until attaining sufficient mass to clear the orbit. Around a star, a hybrid accretion object must attain the nominal mass of a super-Earth to clear its orbit and create a new inner edge to the protoplanetary disk. Then a new round of planetesimal formation can commence, in or between the strongest outer mean motion resonances (MMRs) of the new hybrid-accretion object. In this way, the innermost (anchor) hybrid accretion object spawns a second hybrid accretion object against its strongest outer resonances and so forth, which may form a chain of hybrid-accretion objects from the inside out, like peas-in-a-pod.

¶ Hybrid accretion moons may similarly form around giant planets. The 5 planemo moons of Uranus (Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania and Oberon) are perhaps the best example of a well-behaved moony hybrid-accretion cascade in our solar system.

¶ Sourav Chatterjee and Jonathan C. Tan quantified this form of inside-out planet formation mechanism in a more general form, encompassing either pebble accretion or ∼1 M⊕ planet formation by gravitational instability. “Formation of a series of super-Earth mass planets from pebbles could require initial protoplanetary disks extending to ∼100 AU.” (Chatterjee and Tan 2013)

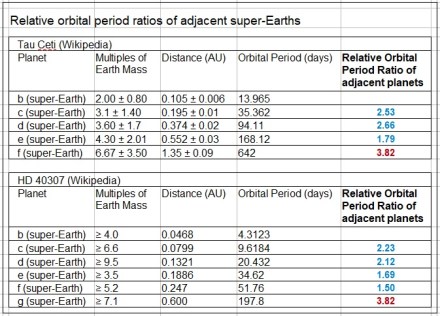

¶ In chains of super-Earths, the outermost planetary pair typically exhibits a greater period ratio than the other adjacent planetary pairs in the same stellar system. This may lend support to inside-out formation mechanism, where only the outermost last-forming super-Earth has not experienced a significant degree of inward migration due to the inward pressure of truncating a massive accretion disk against its outer resonances. See Table 1 for a comparison of the period ratios for 2 chains of super-Earths.

Table 1. Orbital period ratios of adjacent super-Earths. Note the greater orbital period ratio between the outermost adjacent super-Earth pairs (red) compared to inner adjacent super-Earth pairs (blue)

………………..

3. Flip-Flop Fragmentation (FFF)

¶

¶ ‘Flip-flop fragmentation’ (FFF) is an alternative hypothesis for the formation of most star systems with gaseous satellites, potentially forming gaseous satellites by 2 separate but related mechanisms. 1) Hot and cold Jupiters and their diminutives are suggested to primarily form by a flip-flop mechanism, designated, asymmetrical flip-flop fragmentation (asymmetrical FFF), in which a stellar-mass disk fragmentation displaces a planetary-mass prestellar/protostellar object into a planetary satellite orbit. 2) Brown dwarfs and red dwarf satellites, and possibly their diminutives may form when a dynamical bar-mode instability-shaped accretion disk trifurcates into a massive twin pair in orbit around a diminutive protostellar core at the system barycenter by a process designated, symmetrical FFF. A third mechanism for forming gaseous satellites, designated trifurcation, is discussed in § 4.

¶ Asymmetrical FFF is further subdivided into forming hot Jupiters in low ‘hot’ orbits (and their diminutives) and cold Jupiters in high ‘cold’ orbits, and their diminutives. Hot Jupiters are suggested here to for by disk fragmentation of accretion disks and cold Jupiters are suggested here to form by disk fragmentation of pseudodisks (beyond accretion disks).

¶ Symmetrical FFF systems are born as dynamically-unstable nonhierarchical systems that gradually evolve into stable hierarchical systems through orbital interplay that progressively ‘evaporates’ the diminutive prestellar/protostellar central core into a circumbinary orbit, as a ‘companion’, around the much-more-massive twin pair. Finally, the massive twin components of symmetrical FFF systems may be perturbed by their circumbinary companion to spiral-in and merge.

¶ These several mechanisms do not purport to explain all gaseous satellites, where many companion stars have presumably formed by alternative fragmentation mechanisms not explored here, and other mechanisms for forming gaseous exoplanets may also exist.

A counterintuitive protostellar disk discovery:

¶ Planet formation theory is constrained by the mass and evolution of protostellar disks. A counterintuitive discovery (Tychoniec et al., 2018) found decreasing accretion disk mass with protostellar evolution. The study measured a dramatic decrease in dust mass with increasing protostellar age, where measured dust mass is assumed to be a proxy for overall accretion disk mass. Disk dust mass was measured to decrease from 248 M⊕ in Class 0 protostars, to 96 M⊕ in Class I protostars, to 5-15 M⊕ in Class II protostars. And if the youngest (Class 0) protostars have the most massive disks, then a reasonable extrapolation suggests that still-younger prestellar objects might have still more-massive disks. If protostars are steadily accreting while their surrounding accretion disks are rapidly dissipating, then these opposing trends suggests the possibility of an early crossover point, before which accretion disks may be (much) more massive than their diminutive, planetary-mass prestellar/protostellar central cores, resulting in dynamically unstable systems. “The compact components around the Class 0 protostars could be the precursors to these Keplerian disks. However, it is unlikely that such massive rotationally supported disks could be stably supported given the expected low stellar mass for the Class 0 protostars: they should be prone to fragmentation”. (Li et al. 2014)

¶ Another study of 90 protostellar systems finds the highest dust opacity in the youngest Class 0 disks: “The ratio of disk-averaged brightness temperature to predicted dust temperature shows a trend of increasing values toward the youngest Class 0 disks, suggesting higher optical depths in these early stages” (Hsieh et al., 2025), where optical depth presumably correlates with disk mass.

Hot Jupiters Saturns and Neptunes by asymmetrical FFF of protostellar disks:

¶ The Tychoniec et al. (2018) finding of decreasing disk mass with protostellar evolution suggests the possibility of an early crossover point, where the disk mass may be greater than the core mass. If this occurs, the disk’s self-gravity dominates the dynamics of the system. The gravitational potential of the disk itself becomes the primary factor, effectively decoupling the dynamics of the disk from the influence of the central core. This shifts the system from being core-dominated to being disk-dominated, and the central object contributes less to the system’s stability. In a core-dominated system, the disk’s material follows approximately Keplerian motion; however, when the disk dominates, the rotational profile becomes non-Keplerian, reflecting the disk’s self-gravitating structure. Toomre’s Q-criterion governs local instabilities, but for extremely massive disks, the assumption of localized perturbations breaks down, and global effects must be considered. Thus, Toomre’s stability criterion is critical in local disk instability, whereas global effects take over in disk fragmentation. In a disk that is much-more massive than its prestellar/protostellar object, the self-gravity of the entire disk must be considered, while conserving system angular momentum. If the self-gravity of a single inhomogeneity dominates the disk, it will progressively displace the core from the center of rotation, causing the former core to spiral out into a satellite orbit around the much-more massive disk fragmentation, which becomes the new prestellar/protostellar object at the center of rotation. The inward projection of mass that occurs during asymmetrical FFF converts potential energy to kinetic energy in the form of heat, which increases the number of microstates of the system, thereby increasing system entropy, which is thermodynamically favored.

¶ In Fig. 2, a tight knot of hot Jupiters is clustered along the top diagonal line segment demarcating the triangular-shaped exoplanet desert. The negative slope of this hot Jupiter cluster indicates an anticorrelation between mass and orbital distance. Tychoniec et al. (2018) discovery that found decreasing accretion disk mass with protostellar evolution may explain the anticorrelation of mass with orbital distance if the Tychoniec discovery extends into the prestellar realm. Thus, if earlier, lower-mass presolar objects are typically surrounded by more massive accretion disks than older, more-massive presolar objects, then the resulting asymmetrical FFF (disk fragmentation) should inject low mass prestellar objects into higher orbits than higher-mass prestellar objects, partly due to the greater specific angular momentum of more-massive accretion disks, and partly due to the increasing mass of prestellar objects over time, since less-massive planetary satellites need to be injected into higher orbits to have comparable angular momentum to more-massive planetary satellites.

¶ A following subsection will make the argument for 4 Mj being the dividing line between the mass of prestellar objects and protostellar objects. If we name the clustered hot Jupiters with an anticorrelation ‘classical hot Jupiters’, we note from Fig. 2 that a fair number of hot Jupiters lie above the knot of classical hot Jupiters, with a fair number above the purple horizontal line at 4 Mj, presumably dividing former protostars above the line and former prestellar objects below the line. These nonclassical hot Jupiters remain unexplained, although some may have been injected into lower orbits by subsequent episodes of disk fragmentation in systems with multiple instances of asymmetrical FFF.

¶ Cold Jupiters often have sibling cold Jupiters, whereas hot Jupiters and hot/warm Neptunes tend to be solitary gaseous planets, suggesting that disk fragmentation of accretion disks generally only occurs once, whereas disk fragmentation of pseudodisks is more likely to repeat.

¶ The displacement of the former core from the center of rotation by disk fragmentation will not absorb sufficient angular momentum, however, to allow the entire disk to collapse directly into a star, such that the new disk-fragmentation object will necessarily inherit a sizable accretion disk of its own, which will include the former core as a planetary satellite. As the disk-fragmentation object (nascent star) accretes gas from the new disk, its growing mass will cause the inertially-displaced former core to spiral-in over time, ultimately installing the former core in a low ‘hot’ orbit as a hot Jupiter or a warm/hot Neptune- or Saturn-mass planet.

¶ Disk fragmentation of protostellar disks (accretion disks) is suggested here to form hot Jupiters, and disk fragmentation of pseudodisks is suggested below to form cold Jupiters. Accretion disks are known to have elevated dust-to-gas ratios, compared to their natal molecular clouds, which supports the formation of hot Jupiter host stars by disk fragmentation of dusty protostellar disks. the host stars of hot Jupiters are relatively metal rich, [Fe/H] = 0.18 ± 0.13, and the host stars of cold Jupiters are relatively metal poor, [Fe/H] = 0.03±0.18 (Banerjee et al., 2024) The standard model of core accretion turns the finding on its head, by suggesting that star systems with elevated metallicity are more likely to form giant planets, but since hot Jupiters are supposedly born as cold Jupiters that have migrated inward, this explanation does not explain why the stars hosting hot Jupiters should have a higher metallicity than stars hosting cold Jupiters.

¶ This conceptual study makes no pretense of explaining or justifying the orbital radii of hot and cold Jupiters, nor the relative difference in orbital radii between hot and cold Jupiters.

The effect of magnetic fields in forming protostellar disks:

¶ Jeans instability in a dark core causes freefall collapse of dust and gas. A magnetic field with an hourglass B-field morphology channels gas and dust in freefall along magnetic field lines, forming a flattened envelope perpendicular to the field lines known as a ‘pseudodisk’ around the central object. In scenarios where the magnetic field is aligned with the rotation axis, magnetic braking is highly efficient, often leading to the suppression of large, rotationally supported disks—a phenomenon known as the “magnetic braking catastrophe.” However, when there is a significant misalignment between the magnetic field and the rotation axis, the efficiency of magnetic braking decreases, facilitating the formation of larger accretion disks.

¶ In the HH 212 protostellar system, HCO+ indicates infalling with small rotation (i.e., spiraling) in the flattened envelope (pseudodisk) extending out to ~800 AU. “Inside the flattened envelope, a bright compact disk is seen in continuum at the center with an outer radius of ~120 AU (0.3″). This disk is also seen in HCO+ and the HCO+ kinematics shows that the disk is rotating.” “The RSD [rotationally supported disk] is expected to be Keplerian when the mass of the protostar dominates that of the disk.” In order to produce enough disk continuum emission, a jump in density by a factor of 8 is necessary between the pseudodisk and (protostellar) disk, which is consistent with an isothermal shock at the interface. In many models of magnetic core collapse, the magnetic field creates efficient magnetic braking that prevents a RSD from forming, resulting in only a pseudodisk forming around the central protostar.

(Lee et al., 2014)

Cold Jupiters by asymmetrical FFF in pseudodisks:

¶ The bimodal hot and cold Jupiter populations are separated by a 10–100 d orbital-period valley, which presumably indicates formation by separate mechanisms. The standard model of core accretion hypothesizes gas-giant planet formation in the Goldilocks zone beyond the frost line, followed by Type II planetary migration to inject gas-giant planets into low ‘hot’ orbits as ‘hot Jupiters’. By the standard model, the wide gulf between the hot and cold populations requires an unlikely all-or-nothing planetary migration mechanism, resulting in a ‘discreteness problem’. Alternatively, asymmetrical FFF may avoid a discreteness problem, with separate origins for the hot and cold populations, where hot Jupiters form by disk fragmentation of accretion disks and cold Jupiters form by disk fragmentation of more-distant pseudodisks.

¶ Additional evidence for disparate origins for hot and cold Jupiters comes from the disparate metallicity of their host stars, where the host stars of hot Jupiters are relatively metal rich, [Fe/H] = 0.18 ± 0.13, and the host stars of cold Jupiters are relatively metal poor, [Fe/H] = 0.03±0.18 (Banerjee et al., 2024). But this would be the expected outcome for an asymmetrical FFF origin from separate disks, if accretion disks are dustier than pseudodisks.

¶ So, separate origins from separate disks may provide a solution to the discreteness problem. Magnetic fields are known to cause magnetic braking in pseudodisks, which transfers angular momentum outward, creating magnetically-truncated accretion disks that are rotationally supported. When there is a significant misalignment between the magnetic field and the rotation axis, the efficiency of magnetic braking decreases, resulting in larger accretion disks that may form hot Jupiters by disk fragmentation, but when the magnetic field is aligned with the rotation axis, magnetic braking is highly efficient, resulting in magnetic truncation of accretion disks. If a seesaw mechanism creates a proportionally more-massive pseudodisk when its associated accretion disk is magnetically truncated, then there may be potential for disk fragmentation in massive pseudodisks.

¶ The angular momentum of gas in the pseudodisk twists the magnetic field lines, compressing the entrained gas, and if the twisted field lines are anisotropic, then the resulting compressed mass will create an anisotropic mass inhomogeneity, which may inertially displace the central prestellar/protostellar object (core) from the center of rotation. And if the anisotropic inhomogeneity is of sufficient size to cause positive feedback in the core, then the potential for a runaway state exists. One further condition is necessary for a runaway state, which is magnetic reconnection of the twisted field lines that libreates the magnetically-compressed dust and gas, allowing self-gravity to take over. When a disk inhomogeneity is much-more massive than its stellar core, then core-disk feedback will be unable to damp down disk inhomogeneities from undergoing runaway disk fragmentation, presumably resulting in asymmetrical FFF, where the former core is injected into a planetary satellite orbit around the disk-fragmentationj object as a nascent star.

Figure 2: Log-log plot of planetary mass as a function of orbital period:

– Red lines: Relative desert of giant planets with an orbital period of 10–100 days, separating hot Jupiters from cold Jupiters

– Purple line: Relative desert of giant planets with a mass of 4 Mj

– Black dashed line segments, meeting at a right angle: outlines the planetary desert

– Black lines with arrowheads: indicates formational mass and resulting mass

Image credit: Modified from Mazeh, Holczer and Faigler, A&A 589, A75 (2016), Fig.1

¶

Symmetrical FFF:

¶ Neptune-, Saturn- and Jupiter-mass planets have been discovered in circumbinary orbits, but the overwhelming majority of companion objects in hierarchical trinary systems are low-mass stars. “At least 32 sub-stellar companions orbiting stellar or brown-dwarf binaries have been detected to date.” (Mogan and Zanazzi, 2024) This compares with 5,600 exoplanets overall. In the Mogan and Zanazzi (2024) study, the complete absence of planets around sub-seven-day period binaries indicates the relative difficulty of finding circumbinary planets, compared to finding planets around solitary stars. And the Gaia spacecraft, which has examined 2 billion stars overall, discovered only 376 new hierarchical triple system candidates in 2022 (Czavalinga et al., 2023), with the stellar companions all having ≲ 1000 day orbital periods. This low number of circumbinary planets and stars is presumably a reflection on the relative difficulty in discovering circumbinary objects, rather than an indication of their relative abundance. The Gaia survey was not designed to find wide circumbinary companions, but the fact that our nearest neighbor star system, Alpha Centauri, has a wide circumbinary companion with a 550,000 year orbital period, suggests that wide hierarchical triples may be very commonplace.

¶ When a collapsing dark core has particularly high specific angular momentum, or its magnetic fields are unable to effectively project angular momentum outward, the infalling dust and gas may form a bilaterally-symmetrical dynamical bar-mode instability, rather than a radially-symmetrical accretion disk. If such a dynamical bar-mode instability reaches sufficient mass and specific angular momentum for self-gravity to fragment the bar, this study suggests that the outcome will be trifurcation, creating new twin Roche spheres from the bar + the core at the center of rotation, creating a trinary system composed of a twin pair in orbit around a diminutive core in a process designated, symmetrical FFF. Symmetrical FFF is indeed a form of trifurcation (§ 4), in that both mechanisms involve the fragmentation of dynamical bar-mode instabilities into a trinary system, such that symmetrical FFF could alternatively be called ‘zero-generation trifurcation’. And similar to trifurcation, the resulting nonhierarchical trinary system is dynamically unstable, which evolves through a process of orbital interplay into a stable hierarchical system, most typically injecting the former core in a circumbinary orbit around the twin components. Equipartition of kinetic energy in orbital close encounters during orbital interplay tends to transfer orbital energy and angular momentum from the more-massive twin components to the less-massive former core. This gradually ‘evaporates’ the diminutive former core into a circumbinary orbit as a ‘companion’ of the binary pair, creating a stable hierarchical system. The spiral-in of the twin components typically forms a binary pair, but secular perturbation by the companion may cause the binary pair to spiral-in and merge in a luminous red nova, converting the trinary system into a binary system, with the companion being the diminutive partner. Our own solar system presumably formed by symmetrical FFF, followed by 4 generations of trifurcation, followed by the spiral-in merger of the twin components (as former ‘Binary-Sun’) in a luminous red nova (LRN). And the LRN created the ‘solar-merger debris disk’ at 4,567 Ma, which spawned the asteroid belt.

¶ The percentage of binaries increases with stellar mass, which may be explained by the angular momentum of the infalling gas overwhelming the nebular magnetic field that serves to transfer angular momentum outward. Thus, more-massive dark cores tend to have higher angular momentum accretion disks, which deform into dynamical bar-mode instabilities and beyond that into dumbbell configurations. dynamical bar-mode instability presumably forms cores at the center of rotation, but the most massive systems with the highest angular momentum that exhibit a dumbbell configuration may fail to form central cores at the center of rotation (the system barycenter). So the most massive stellar systems with the highest specific angular momentum that create dumbbell-shaped ‘accretion disks’ may be born as binary systems without central cores, and therefore are not symmetrical FFF systems, whereas less-massive systems with dynamical bar-mode instability-shaped ‘accretion disks’ presumably form trinary systems by symmetrical FFF.

¶ Some number of the most-massive ‘cold Jupiters in Fig. 2 may have formed by symmetrical FFF, potentially followed by the spiral-in merger of the twin components, leaving a companion orbiting a solitary star, and since symmetrical FFF systems necessarily have high specific angular momentum compared to asymmetrical FFF systems, companions formed by symmetrical FFF should have particularly high (cold) orbits. Indeed, the ‘brown dwarf desert’ below 5 AU may be explained by brown dwarf formation by symmetrical FFF, followed by the spiral-in merger of the twin components, in the case of solitary star systems with brown dwarfs. In addition to forming brown dwarfs as the central protostellar cores, brown dwarfs can also apparently form in binary pairs as the much-more-massive twin components in symmetrical FFF systems, and a new study has found super-Jupiter-mass binary pairs. A recent study (Pearson and McCaughrean, 2023) discovered 540 planetary-mass candidates with masses down to 0.6 Jupiter masses in the Trapezium Cluster, and surprisingly, 9% of these planetary-mass objects are in wide binaries, which challenges current theories of both star and planet formation. The term ‘JuMBOs’ was coined for these Jupiter Mass Binary Objects. A follow up study by Diamond and Park er (2024) of the JuMBOs in Orion Nebula suggests that super-Jupiter-mass binary pairs may be the result of photoerosion by nearby hot stars that quenched star formation in its earliest stages by stripping away the surrounding infalling envelopes. The binary separation of JuMBOs matches the typical Gaussian distribution of A-type star binaries, supporting the photoerosion supposition. If this is the case, then binary brown dwarf systems may be the lowest-mass systems formed by symmetrical FFF without photoerosion.

¶ Our own solar system presumably formed by symmetrical FFF, creating a twin stellar pair, designated ‘Binary-Sun’, and a low-mass brown dwarf core, designated ‘Brown Dwarf’. The Alpha Centauri system presumably also formed by symmetrical FFF, with twice the mass of our solar system and much-greater angular momentum. If our solar system and our nearest stellar neighbor both formed by the same mechanism, then symmetrical FFF may be one of the most prevalent stellar formation mechanisms going.

¶ Similar size and color binary Kuiper belt objects and similar size binary asteroids may indicate that symmetrical FFF may be the typical outcome of streaming instability. The Pluto system is amenable to a symmetrical FFF origin, with Pluto and Charon as twin components. Then the former central core of the system appears to have undergone 2 generations of trifurcation, with Nix-Hydra as 1st-generation trifurcation twins and Styx-Kerberos as 2nd-generation twins.

(Mini)-Neptune- and Saturn-mass planets in relation to the exoplanet desert:

¶ Interstellar gas experiences a degree of pressure support during Jeans instability freefall, such that dust and ice grains have a higher terminal velocity than gas and may accumulate at the center of freefall, disproportionate to the system metallicity. And as freefall increases gas density in the central core, it also increases the partial pressure of volatiles, promoting their condensation onto dust grains. Thus, very-early prestellar objects may form rocky-icy centers before the gas even becomes opaque to infrared radiation at the first hydrostatic core phase.

¶ The relative prevalence of Neptune-mass planets compared to Saturn-mass planets, as apparent in Fig. 2, suggests the possibility that (mini-)Neptunes may have formed as Saturn-mass prestellar objects that lost the bulk of their gaseous component in the upheaval of disk fragmentation, potentially causing Saturn-mass prestellar objects to dissipate into Neptunes or mini-Neptunes. The vertical black arrows in Fig. 2 indicate the suggested Saturn-mass origin of some of the Neptune-mass planets in the 10–100 d orbital period valley, prior to losing the bulk of their gaseous component, suggesting that Saturn-mass planets are not as formationally scarce as they are observationally scarce. This could explain the relative dearth of Saturn-mass exoplanets in the hot Jupiter population derived from asymmetrical FFF of protostellar disks, but the same does not appear to be true in the cold Jupiter population derived from asymmetrical FFF of pseudodisks.

Conservation of angular momentum during asymmetrical FFF:

¶ In rotationally-supported systems, such as protostellar disks, the specific angular momentum

increases with the square root of the radius. So, if a prestellar system with a protostellar disk measuring in the 10s of AU transforms into a hot Jupiter planet with a semimajor axis measured in 10ths to 100ths of an AU, then there must be some form of high-angular momentum compensation to conserve system angular momentum. This requires a mechanism to imbue a percentage of the disk with substantially-greater angular momentum, likely entailing high-velocity outflows with escape velocity from the system. The standard model similarly requires an outward transfer of angular momentum in an accretion disk to enable the inward migration of a planet.

4 Jupiter mass (Mj) giant-planet valley:

¶ Santos et al. (2017) finds a relative scarcity (a valley) of gas-giant exoplanets, with a mass of about 4 Mj.

¶ The most noteworthy occurrence in the prestellar phase is the formation of the first hydrostatic core (FHSC), which marks the transition from prestellar to protostellar objects. As gas falls onto a prestellar object, its potential energy is radiated away as infrared photons, but when it reaches a critical density, the prestellar object becomes optically opaque in the infrared, causing its temperature to rise, which results in hydrostatic pressure that supports the gas against gravitational collapse, forming a FHSC of brief duration.

¶ Gas falling onto the FHSC from the accretion disk creates a shock front that extends to a radius of ~ 5–10 AU (Tsitali et al. 2013). This study suggests that this extreme pithiness may cause a FHSC to viscously engage with the surrounding accretion disk, temporarily damping down the positive disk-core feedback necessary for runaway disk instability, resulting in a temporal hiatus in asymmetrical FFF. The mass of the FHSC is not well constrained observationally or theoretically, with rotation and magnetic fields greatly increasing its theoretical mass above the simple solution calculated by Larson (1969) of 1 Mj, but the importance for this purpose is the resultant mass of the inertially displaced prestellar object after FFF, which is presumed to create the 4 Mj gas-giant planet valley. Bate (2011) predicts a FHSC mass of 5 Mj for nonrotating cores, which suggests the possibility that rotation causes mass loss approximately down to the nonrotating solution for FHSCs.

¶ The duration of the FHSC is calculated to last a few hundred to a few thousand years (Young, 2023), depending on rotation and magnetic fields, with the short duration creating a narrow valley.

L1448 IRS3B (Fig. 1):

¶ The triple star system, L1448 IRS3B, is suggested here to have been formed by symmetrical FFF, where the diminutive former core outshines its more-massive twin siblings, due to its more advanced development. This triple star system is composed of a similar-sized binary pair, IRS3B-a & IRS3B-b, with a combined mass of ~1 M☉ in a 61 AU binary orbit, and a distant tertiary companion, IRS3B-c, with a minimum mass of ~0.085 M☉ in a 183 AU circumbinary orbit around the binary pair. This system may become more hierarchical over time, coming to resemble the Alpha Centauri system at half the mass. “Thus, we expect the [L1448 IRS3B] orbits to evolve on rapid timescales (with respect to the expected stellar lifetime), especially as the disk dissipates. A natural outcome of this dynamical instability is the formation of a more hierarchical system with a tighter (few AU) inner pair and wider (100s to 1,000s AU) tertiary, consistent with observed triple systems.” (Tobin et al. 2016)

¶ The tertiary protostar, IRS3B-c, is embedded in a spiral arm of the outer disk, which has an estimated mass of 0.3 M☉. The standard model of companion star formation, expressed in the Tobin paper, suggests that IRS3B-c formed in situ by gravitational instability from the spiral disk, making IRS3B-c younger than IRS3B-a & IRS3B-b; however, IRS3B-c is brighter at 1.3 mm and 8 mm than its much more massive siblings, which is apparent in Fig. 1. Alternatively, the brighter, tertiary companion supports formation by symmetrical FFF, with the diminutive companion as the more-evolved central protostar of the system.

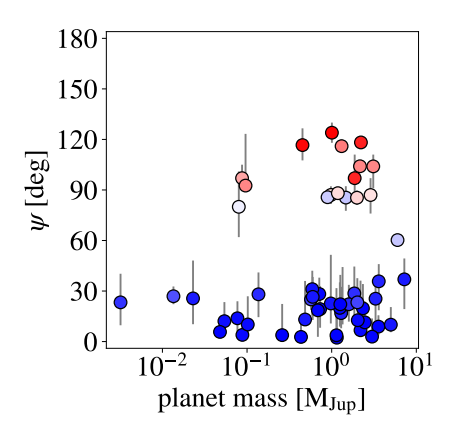

Hot Jupiters and hot Neptunes in polar orbits:

¶ Hot Jupiters exhibit bimodal obliquity. Hot Jupiter orbits that are misaligned with their host stars “show a preference for nearly perpendicular orbits (ψ = 80 − 125°) that seems unlikely to be a statistical fluke” (Albrecht et al., 2021) (Fig. 3). Another article that discovered two hot Neptunes in polar orbits states, “we performed a hierarchical Bayesian modeling of the true obliquity distribution of Neptunes and found suggestive evidence for a higher preponderance of polar orbits of hot Neptunes compared to Jupiters” (Espinoza-Retamal et al. 2024).

¶ This discovery of star systems with giant planets in low, hot polar orbits is suggested here to be formational, and not due to subsequent migration, as is commonly assumed. Since stars formed by asymmetrical FFF are younger than their planets, and since their giant planets have much-greater orbital angular momentum than the rotational angular momentum of their stellar hosts, it’s likely that collapsing disk fragmentation objects have a propensity to torque their rotational axes perpendicular to the orbit of inertially-displaced former stellar cores.

¶ In asymmetrical FFF, the former prestellar core and the nascent disk-fragmentation object creates a system barycenter, which may interfere with the formation of a local center of rotation in the contracting disk-fragmentation object when it’s in the same plane as the barycenter. In this context, a lower energy state may be attained by torquing the rotation axis of the disk-fragmentation object perpendicular to the barycenter rotation axis, allowing for the more-rapid contraction of the disk-fragmentation object into a nascent star. Torquing the spin axis of the disk instability object may occur gradually by precession of the collapsing disk-fragmentation object by a reaction against the residual protostellar disk and the former prestellar core in its nascent satellite orbit. Since giant planets contain the vast majority of the angular momentum in stellar systems, the much-higher angular momentum of the former core torques the much-more-massive nascent disk-fragmentation object into a perpendicular orientation. In order to compete for the center of rotation, the former prestellar core must be close to the nascent disk-fragmentation object, which is why only hot Jupiters are commonly found in polar orbits.

¶ Systems that fail to undergo perpendicular torquing of their disk-fragmentation objects may retain more mass in their protostellar disks and thus may be susceptible to further occurrences of asymmetrical FFF, potentially forming multiple hot Jupiters. This suggests that perpendicular torquing of a disk-fragmentation object may generally preclude further instances of disk fragmentation by more efficiently incorporating the dust and gas of the fragmented accretion disk, which predicts that in systems with multiple hot Jupiters, all or none will be found in polar orbits. The 3 super-puff planets in the Kepler-51 system (Table 2) may be a good test of this principle. Two of the planets have perfect 90° obliquity (Kepler-51b & Kepler-51d). If the third super-puff planet is also discovered to have a polar orbit, this may lend support to this hypothesis and to the torquing of the rotation axis of the stellar component rather than the planetary component.

¶

Galactic FFF:

¶ FFF might also explain the formation of large spiral and elliptical galaxies from primordial dwarf galaxies formed prior to recombination. (See: Two Epochs of Baryonic Dark Matter, with Free-floating Super-puff-like Planets as the Second and Present Epoch). This ideology suggests that spiral galaxies may have formed by asymmetrical FFF through an inertial flip-flop of a diminutive core formed at the center of rotation. Similarly, giant elliptical galaxies may have formed by symmetrical FFF, followed by the spiral-in merger of twin components.

¶ Galactic asymmetrical FFF presumably forms by asymmetrical FFF, where the Large Magellanic Cloud may be the former core of the disk of primordial dwarf galaxies that formed the Milky Way galaxy. Potentially lending support to this hypothesis is the resemblance of hot Jupiters in polar orbits with vast polar structure (VPOS) or polar disk of satellites (DoS) surrounding the Milky Way and other nearby galaxies, suggesting a common formation mechanism in which the contracting disk-fragmentation object torques itself perpendicular to the system barycenter to attain a lower energy state.

Symmetrical FFF planets, analogous to trifurcation moons (§ 5):

¶ This study suggests that trifurcation also creates a twin pair of trifurcation moons in each trifurcation generation, which are gravitationally bound to their respective twin components. This suggests a refinement to trifurcation, designated ‘trifurcation+2’, with the +2 encompassing the twin trifurcation moons. And because of the similarity of symmetrical FFF to trifurcation by way of a common dynamical bar-mode instability, symmetrical FFF may create 2 symmetrical FFF planets, 1 for each twin component.

¶ Computer simulations indicate spiral tails emanating from the ends of the bar in dynamical bar-mode instabilities. When the bar gravitationally trifurcates, the twin spiral tails may detach from the trifurcating bar to form their own Roche spheres. In the case of trifurcation where the twin components are planetary in mass, gravitational collapse of the spiral tails are designated as ‘trifurcation moons’. In the case of symmetrical FFF where the twin components are stellar in mass, gravitational collapse of the spiral tails are designated ‘symmetrical FFF planets’.

¶ In this regard, if Alpha Centauri indeed formed by symmetrical FFF, then each twin component should have formed with a symmetrical FFF (S-type) planet. The twin binary stars of the Alpha Centauri system may each have a planet, although neither planet has been confirmed, and these unconfirmed planets are of very different sizes and orbit at very different distances from their host stars. The unconfirmed planet, ‘Candidate 1’, of Alpha Centauri A is determined to have a mass range of 9–35 M🜨, at a semimajor axis of 1.1 AU, and the still-less-confirmed possible planet around Alpha Centauri B is determined to have a radius of ~ 0.92 R🜨 and a median likely orbit of 12.4 days (Demory et al., 2015).

¶ Objects formed by the gravitational collapse of spiral tails during trifurcation of dynamical bar-mode instabilities are born without any angular momentum with respect to their trifurcation twins. In the case of trifurcation moons, buffeting by the much-more-massive twin components that induced trifurcation gives the system an initial kick that presumably injects 1 moon into a prograde orbit around its trifurcation twin and (necessarily) injects the other moon into a retrograde orbit around its corresponding trifurcation twin. In the 4th-generation trifurcation in our solar system, Earth acquired the prograde Moon Luna, and Venus presumably acquired a retrograde moon that spiraled in and merged with Venus, possibly at 579 Ma, causing the Venusian cataclysm. But in the case of symmetrical FFF, there are no larger-mass objects to kick the twin components to initiate orbital rotation of the twin symmetrical FFF planets, although the former core, Proxima Centauri, may have provided small kicks or the heterogeneity of the fragmenting disk could have provided the necessary kick to prevent the planets from falling into their twin components.

………………..

4. Trifurcation by centrifugal fragmentation

¶

¶ In a high angular momentum prestellar/protostellar system in which the accretion disk is much more massive than its diminutive core, the disk has inertial dominance of the system, which promotes stellar-mass disk instability. The type of disk instability may depend on the mode of a (spiral) density wave resident in the accretion disk, with asymmetrical (m = 1 mode) density waves forming solitary disk-instability objects by asymmetrical FFF, and symmetrical (m = 2 mode) density waves collapsing to form twin disk-instability objects by symmetrical FFF.

¶ Asymmetrical FFF inertially displaces the stellar core from the center of mass of the system as the system becomes progressively more asymmetrical during the incipient disk instability, but symmetrical FFF preserves the bilateral symmetry of the system, with the protostellar core remaining at the center of the system; however, the much-greater overlying mass of the twin disk-instability objects is dynamically unstable, resulting in subsequent chaotic orbital interplay that progressively projects mass inward.

First-generation trifurcation:

¶ Symmetrical FFF creates twin stellar-mass disk-instability objects in orbit around a diminutive protostellar core. The much greater overlying mass of the twin disk-instability objects constitutes a dynamically-unstable (non-hierarchical) trinary system, which is gradually resolved by orbital interplay into a stable hierarchical system, but another consequence of orbital interplay may be centrifugal-fragmentation of the protostellar core by way of trifurcation. Orbital interplay causes equipartition of kinetic energy, wherein kinetic energy is transferred from the much-more-massive disk-instability objects to the diminutive protostellar core, and if this kinetic energy transfer includes rotational energy, then this study suggests that orbital interplay in symmetrical FFF systems may induce centrifugal fragmentation of protostellar cores. Trifurcation implies centrifugal fragmentation into 3 components, creating a trinary subsystem that locally decreases the trifurcation subsystem entropy.

Equipartition of kinetic energy in 2 spatial and 1 rotational degrees of freedom:

¶ Globular clusters composed of stars of varying masses undergoing mass segregation, also called core collapse, exhibit a property known as negative heat capacity, where the core heats up as it loses energy to the periphery. The mechanism driving mass segregation, which projects mass inward, is equipartition of kinetic energy through gravitational close encounters, which tends to equalize the kinetic energy in each degree of freedom. Since velocity has an inverse relation to the square root of mass in kinetic energy, equipartition of kinetic energy creates disparate velocities between objects of disparate masses, which projects mass inward. Equipartition of kinetic energy is the principle used to extract orbital energy from planets by interplanetary spacecraft in a process known as ‘gravitational slingshot’ or ‘gravity assist’, in which the spacecraft parasitizes the orbital energy of the planet by means of a gravitational interaction. Multiple star systems that have undergone mass segregation are said to be hierarchical, but symmetrical FFF systems and newly trifurcated systems are born nonhierarchical and evolve toward hierarchical equilibrium by orbital interplay governed by equipartition of kinetic energy.

¶ Because rotation is a degree of freedom, equipartition of kinetic energy will necessarily cause a spin up of less-massive objects in corotating systems during orbital close encounters. Indeed, Scheeres et al. (2000) calculates that the rotation rate of asteroids tends to increase in gravitational encounters with other asteroids and planets, providing evidence for the rotational spin up underpinning trifurcation. Symmetrical FFF forms prestellar/protostellar cores at the center of rotation that are born with zero kinetic energy in the 2 spatial degrees of freedom in a coplanar system, but they are born with high prograde spin rates in the rotational degree of freedom. By comparison, the twin stellar-mass disk-instability siblings of prestellar/protostellar cores are born with high kinetic energy in the 2 spatial dimensions and are presumably also born with high prograde spin rates. Because prestellar/protostellar cores are already rapidly spinning at formation, any additional spin up from gravitational interactions with the twin disk-instability objects will cause early distortion into a triaxial shape on the way to centrifugal fragmentation. And trifurcated systems are merely miniature versions of symmetrical FFF systems.

¶ Rotation causes a planemo object to distort into an oblate sphere. Additional spin up distorts the oblate sphere into a triaxial Jacobi ellipsoid. Still greater spin up forms a dynamical bar-mode instability. This study suggests that the centrifugal failure mode of a dynamical bar-mode instability is fragmentation into 3 components, hence trifurcation, wherein self-gravity fragments the bar, causing the opposing ends to pinch off into independent Roche spheres to create a twin pair of objects in orbit around the diminutive residual core remaining at the center of rotation. Thus, a single Roche sphere trifurcates into a gravitationally bound Keplerian system composed of 2 new twin Roche spheres in orbit around the diminutive residual core at the center of rotation, which constitutes the third Roche sphere. (Additionally, dynamical bar-mode instabilities exhibit trailing tails that lag behind the ends of the bar. These trailing tails constitute additional masses that may pinch off to form independent moony Roche spheres that remain gravitationally bound to their respective twin trifurcation components as ‘trifurcation moons’ § 5.)

¶ At the moment of trifurcation, the trinary components resemble a smaller (Mini-Me) version of the original symmetrical FFF system, with a massive twin-binary pair orbiting a diminutive residual core. And like symmetrical FFF, the trifurcated trinary components constitute a dynamically unstable system that’s resolved by orbital interplay, with accompanying spin up of the residual core, promoting next-generation trifurcation, potentially creating a cascade of successively smaller binary pairs, like Russian nesting dolls. Our solar system retained 3 of the 4 sets of twin binary pairs from 4 generations of trifurcation, only losing the largest twin binary pair, Binary-Companion.