Hickory Run boulder field, Hickory Run State Park Pennsylvania

¶

1. Introduction

2. Ringing Rocks, Wikipedia entry

3. Multiple primary impacts on the Laurentide ice sheet

4. Allochthonous blockfields

5. Incised surface features on impact boulder field boulders

6. Secondary impact rock scale

7. Magnetic spherules in Pleistocene tusk and bone in Clovis chert flakes

8. Discussion

References

Abstract:

¶ Discrete boulder fields attributed to the last glacial maximum (LGM) are suggested here to have had a catastrophic origin in common with the ~ 500,000 Carolina bays. According one version of the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis (YDIH), 12.8 ka, Firestone (2007) hypothesized Carolina bays to be secondary impact structures from an ejecta curtain of Laurentide ice-sheet fragments kicked into ballistic trajectories by multiple primary bolide impacts or airbursts on or over the Laurentide ice sheet in the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay regions. And where ballistic trajectories of ice-sheet fragments fell short of coastal regions and landed on thin soil, the target bedrock may have experienced secondary impact brecciation, in some cases forming discrete ‘YD impact boulder fields’ that are still devoid of vegetative cover almost 13 thousand years later.

¶ Some hypothesized YD impact bounder fields appear to be in situ bounder fields, formed directly over top of ground zero as “autochthonous blockfields”, of which Ringing Rocks type boulder fields may be the best examples. Alternatively, when secondary impacts occurred on sloping ground, the brecciated boulders may have flowed downhill as rockslides or debris flows, forming “allochthonous blockfields”, like Hickory Run boulder field.

¶ In addition to bedrock brecciation, atmospheric ablation of secondary ice-sheet fragments during ballistic reentry may have created streams of super-high-velocity fluid droplets that could have scoured out deeply-incised surface features found on boulder surfaces in several discrete boulder fields in the form of pits and striations and potholes. And the slurries scoured from these incised surface features would have splattered nearby rocks and could have hardened into rock scale, under the high temperature and shock wave pressure conditions of secondary impacts. Images of brown nodular rock scale are presented as evidence.

¶ Some diabase boulders in Ringing Rocks type boulder fields exhibit the ability to ring when sharply struck, and the absence of this property in diabase boulders outside these discrete boulder fields suggests extraordinary formational conditions. Curiously, “live” boulders that ring can be transformed into “dead” rocks that no longer ring by cutting or breaking live boulders. Surface stress is relieved by cutting or breakage, whereas cut or broken rocks should retain the internal bulk stress acquired by intrusive igneous rock at formation. A catastrophic secondary impact causing bedrock brecciation and surface stressing by super-high-pressure shock waves may explain the evidence.

………………..

1. Introduction

Standard model for blockfields attributed to the Last Glacial Maximum:

¶ Several very prominent boulder fields in Pennsylvania, also known as blockfields, are often attributed to processes active during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), which occurred more than 11.7 ka. The most common understanding for the formation of these relatively-young boulder fields is fracturing by ‘frost wedging’ due to periglacial freeze-thaw cycles, which involves water freezing and expanding in the cracks of bedrock, fracturing the bedrock into blocks.

¶ However, this common understanding among many geologists is suggested by Boelhouwers (2004) to be a “geomyth”.

The manner in which the perceived dominance of frost weathering has established and maintained itself in periglacial geomorphology has all the characteristics of Dickinson’s “geomyth.” Autochthonous blockfields can no longer be viewed as a diagnostic landform of periglacial environments and this leads to a further critical questioning of the dominance of frost weathering in periglacial landscape development, a point reiterated on several occasions (…). The long-time perceived association of blockfields with frost action, so fundamental to the perceived efficacy of frost weathering, must be rejected in the light of the above discussion. Instead, blockfields and their features reflect complex and diverse process and climatic histories that defy straightforward palaeoclimatic associations.

(Boelhouwers, 2004)

Beolhouwers (2004) goes on to say that macrogelivation (frost wedging) can only exploit already existing fractures, and that microgelivation (a micro version of frost wedging) only occurs in porous rock. “Generally however, blockfields are invariably associated with highly resistant lithologies, typically Paleozoic quartzites, granites, highly metamorphic rocks such as gneisses, or fine- to medium-grained basalts. These rock types are characterized by low primary porosities and are considered non-frost susceptible (…).” So periglacial frost wedging for the origin of blockfields is far from settled science.

¶ In the standard model, blockfields can either be generated by in situ weathering of resistant bedrock, forming ‘autochthonous blockfields’, or from transported material, forming ‘allochthonous blockfields’. Conventionally, allochthonous blockfields were transported downhill either gradually by ‘solifluction’, or suddenly by ‘gellifluction’, presumably during periglacial conditions, or by ‘creep’ without periglacial conditions. The frozen subsurface acted as a barrier to water percolation, trapping the water in the thawed soil at the surface, creating slick greasy soil over a frozen subsurface during seasonal thaw cycles. Solifluction suggests a gradual creep of boulders downhill, whereas gellifluction suggests catastrophic liquefaction of waterlogged soil, possibly causing rockslides or debris flows.

Alternative catastrophic hypothesis for LGM blockfields:

¶ Alternatively, this study suggests that (young) boulder fields attributed to the LGM are the indirect result of the Younger Dryas impact hypothesis (YDIH). Evidence of a Younger Dryas (YD) impact or airburst is revealed in Greenland ice sheet cores in the form of a platinum spike, circa 12.8 ka (Petaev et al., 2013). Additionally, a thin layer of magnetic grains, microspherules, nanodiamonds, and glass-like carbon have been unearthed at various locations across North America, Europe and beyond, generally overlain by a ‘black mat’ with a high carbon content. The black mat is nearly coincident with megafauna extinction in North America and the disappearance of the Clovis civilization (Firestone et al., 2007), and “extinct megafauna and Clovis tools occur only beneath this black layer and not within or above it” (Firestone, 2009).

¶ Moore et al. (2024) found that sediment sequences spanning the Younger Dryas boundary YDB) found peak abundances in platinum, microspherules, meltglass, and quartz grains with shock fractures containing amorphous silica, which is consistent with ~ 50 other sites across North and South America, Europe, Asia and the Greenland ice sheet. “We also find in the YDB high-temperature melted chromferide, zircon, quartz, titanomagnetite, ulvöspinel, magnetite, native iron, and PGEs with equilibrium melting points (∼1,250° to 3,053°C) that rule out anthropogenic origins for YDB microspherules.”

¶ An impact hypothesis for large, shallow oval depressions known as Carolina bays originated in the 1940s. Then a more-plausible secondary impact hypothesis was advanced in the 21st century, suggesting a primary impact on or over the Laurentide ice sheet that showered North America and likely beyond with an ejecta curtain of secondary ice-sheet fragments (Firestone, West and Warwick-Smith, 2006). Carolina bays are a series of ~ 500,000 oval depressions that range in size from 50 m to 10 km in length that are concentrated along the Atlantic seaboard and the coastal plain of the Gulf of Mexico. The long axes of the Carolina bays presumably point back to one or more primary bolide impacts on the former Laurentide ice sheet in the Great Lakes Region and the Hudson Bay Region that lofted massive ice-sheet fragments into ballistic trajectories 1000 or more kilometers to form elongated secondary-impact structures, when they landed on soft waterlogged soil along the coastal plains.

¶ If the YD-impact ejecta curtain was at all isotropic, then the rest of the North American continent was similarly showered with secondary impacts, but the harder inland terrain apparently experienced less physical damage, and/or subsequent erosion has largely erased the damage. But there may be a few instances where damage is still clearly evident in the form of impact brecciated bedrock, forming discrete boulder fields. Ballistic ice-sheet fragments traveling several kilometers per second may have fractured target bedrock, in some places forming autochthonous blockfields overtop of their impact sites, and in other places initiating downhill rockslides or debris flows to concentrate boulders downhill from their secondary impact sites as allochthonous blockfields.

¶ Note that the vast majority of bedrock brecciated by secondary impacts has not formed boulder fields, with many of the boulders covered with subsoil and topsoil. In and around West Conshohocken, PA, large diabase boulders are unearthed when digging basements, which the homeowners often display in their front yards, and many boulders have been dug up in Calvery Cemetery (Fig. 23). Note the particularly sharp corners and orange weathering rind on diabase boulders from the West Conshohocken Area (Figs. 23 –24).

¶ Boulder fields may form in sedimentary, igneous or metamorphic rock. In the Pennsylvania boulder fields discussed in this study, Ringing Rocks type boulder fields are composed of intrusive igneous diabase, Hickory Run boulder field is composed of sedimentary sandstone and conglomerate, and Blue Rocks boulder field is composed of metamorphic quartzite.

Diabase boulder fields § 2:

¶ The Ringing Rocks type boulder fields warrant particular scrutiny for several reasons. The lack of porosity and lack of natural cleavage planes of intrusive igneous diabase, also known as dolerite, significantly constrains possible brecciation mechanisms and the hardness and toughness readily retains surface features. And igneous rock develops chemical weathering rinds, allowing for relative exposure age determinations between disparate sets of igneous boulders of similar type. And finally, the sonorous property of ‘Ringing Rocks’ may offer an additional clue.

¶ The Triassic-Jurassic diabase that forms the geological basis of the Ringing Rocks is a part of the intrusive suite of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP). This magmatism, associated with the rifting of Pangea, occurred during the late Triassic to early Jurassic period. Eight diabase sheets and one dike in the central Newark basin make up a single megasheet that extends for 150 km (Husch, 1992), which intruded into the sedimentary formations of the Newark Supergroup. But curiously, at least several of the ringing diabase boulder fields are located in the narrow basal olivine unit, containing olivine and pyroxene cumulates from the diabase sills, which provides a conundrum for both gradualistic and catastrophic hypotheses. This suggests a possible percussion effect of a thin basal olivine unit over metamorphosed rock of the Newark Supergroup in a catastrophic secondary impact scenario.

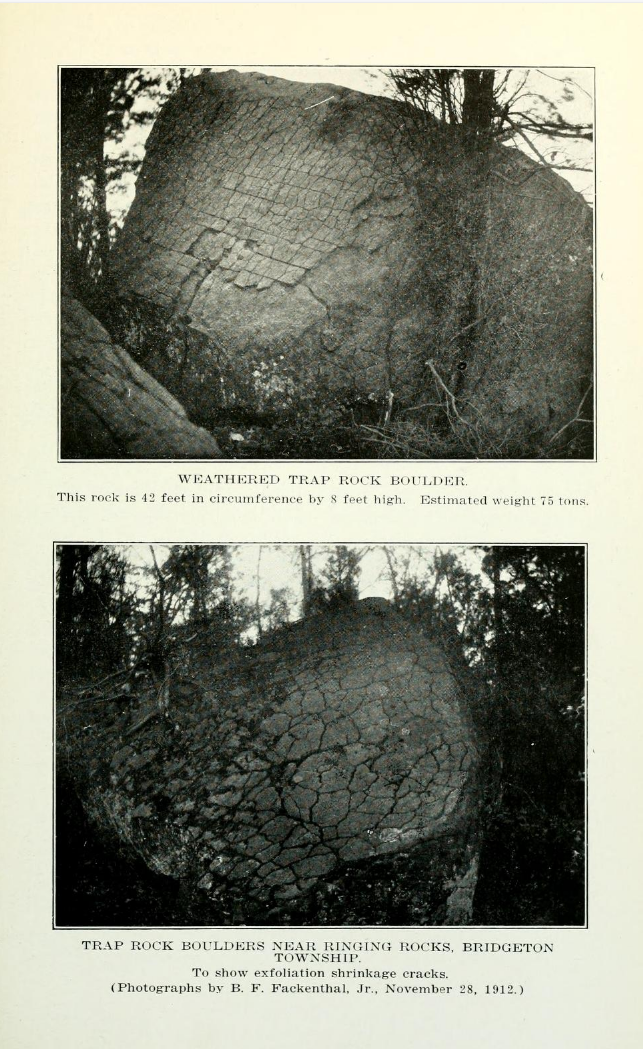

¶ The slow weathering rate of diabase boulders can be inferred from the millimeter-scale thickness of the weathering patina on the several diabase boulder fields in Eastern Pennsylvania attributed to the LGM. By contrast, the boulders in the woods surrounding the Ringing Rocks boulder field in Upper Black Eddy, PA are are intermittently covered with centimeter-scale weathering rinds and exhibit rounded corners that represent many sequential episodes of rind exfoliation (Psilovikos and Van Houten, 1982)—examples of weathering rinds on diabase boulders from the woods surrounding the discrete Ringing Rocks boulder field (Fig. 28). The simplest explanation for the weathering disparity is a much younger age for the discrete boulder field, which is intuitively suggestive of a catastrophic origin.

¶ Only diabase boulders in ‘young’ discrete boulder fields attributed to the LGM exhibit an ability to ring when sharply struck. It’s well known that “live” boulders that ring can be “deadened” by breaking or cutting the boulders, suggesting that the ringing property is due to surface stress, rather than a bulk stress property, which sawed and broken rocks would still retain. And surface stress is a property that could only be acquired at or after brecciation, which is consistent with a catastrophic secondary impact, accompanied by super-high-pressure shock waves.

Incised surface features § 4:

¶ Another peculiar aspect of young boulder fields is deeply incised surface features, described here as pits, striations and potholes in sunken relief (Figs. 5 –12).

¶ Pitting has been attributed to “solution by rain in the absence of forest shelter and a mantle of soil” (Psilovikos and Houten 1982), and yet boulders in diabase boulder fields attributed to the LGM exhibit only a thin uniform weathering patina, rather than the wide disparity of weathering thickness necessary to explain deep pitting by that mechanism. And the means by which weathering products could have been continuously purged from pits when thick cracked weathering rinds are still present on boulders in the woods beyond the discrete Ringing Rocks boulder field requires explaining. And the mechanism by which the weathering products could have been so uniformly purged from pits in discrete boulder fields, when thick cracked weathering rinds are still present on boulder surfaces in the woods beyond the discrete Ringing Rocks boulder field requires an explanation.

¶ Significantly, these surface features appear to be confined to boulders in discrete ‘young’ boulder fields attributed to the LGM. This study suggests that ablative erosion of secondary impact ice-sheet fragments on ballistic trajectories sloughed off super-high-velocity droplets that scoured deep pits and striations in impact-brecciated boulder surfaces, like industrial sand blasting or water jet cutting. Boulders with pitted surfaces typically exhibit pitting on only 1 or 2 faces, with the other faces of the same boulder free of pitting.

Rock scale § 5:

¶ If secondary impacts scoured pits, potholes and striations into rock surfaces, the scoured slurry would have splattered on adjacent rocks, which could have hardened into persistent rock scale under high-temperature high-pressure conditions. And indeed, unusual nodular brown rock scale can be found across East-central Pennsylvania on sedimentary rock and quartzite or quartz pegmatite, which are rock types not known for developing weathering rinds (Figs. 13 –20). Splattering from line-of-sight scouring suggests an autochthonous source for rock scale, with a composition derived from the target bedrock.

¶ YD impact rock scale takes YD impact dynamics to the tertiary level:

– Ultra-high-velocity primary bolide impacts or airbursts at interplanetary speeds

– Super-high-velocity secondary impacts from an ejecta curtain of ice-sheet fragments in ballistic trajectories at several kilometers per second

– Very-high-velocity tertiary splattering of rock surfaces by slurries of scoured material, forming YD impact rock scale, with an autochthonous composition

Basal olivine unit of diabase sheets:

¶ Ringing Rocks type boulder fields apparently formed over basal olivine units of diabase sheets (Fig. 2). Triassic-Jurassic diabase that intruded into the Newark Supergroup differentiated into a 10–15 ft (3.0–4.6 m) thick basal olivine unit, containing cumulate olivine and pyroxene phenocrysts. And significantly, at least several of the sonorous diabase boulder fields occur on exposures of the basal olivine unit, where the surface slope is in the same direction as the dip in the diabase sheet, maximizing the exposure of the basal olivine unit (McCray, 1997). Indeed, both the standard model and the alternative impact hypothesis are challenged by this coincidence.

¶ While secondary impacts of ballistic ice-sheet fragments may be significantly anisotropic over large distances, they should be essentially random over the small distances of local diabase exposures. To explain the disparity between the low number of discrete boulder fields and the high number of Carolina bays (~ 500,000), despite the vastly-greater inland land mass, compared to the coastal regions where Carolina bays are found, suggests that discrete boulder fields likely required multiple favorable conditions for formation. A relatively-thin basal olivine unit over the underlying contact-metamorphic flint-like hornfels suggests a possibility. An acoustic impedance contrast between the olivine basal unit and the underlying hornfels of the Newark Supergroup might have partially reflected the incoming impact shock wave back from the interface, and the differential pressure and impulse load of colliding shock waves from opposing directions may have particularly promoted brecciation. But impacts on thicker diabase exposures of the overlying ‘regular’ diabase unit may have sufficiently attenuated the shock wave such that the reflected shock wave from the diabase-hornfels interface was insufficient to promote efficient brecciation.

¶ Not only do the basal olivine units appear to preferentially ‘spawn’ boulder fields, compared to the greater diabase sheet, but the boulders thus formed acquire an ability to ring in the audible range when sharply struck. The Pennsylvania Ringing Rocks (McCray, 1997) and Montana ringing rocks (Butler, 1983) both share a mafic composition with cumulate phenocrysts, which may be significant for forming sonorous rocks, but it’s only 2 data points.

………………..

2. Ringing Rocks, Wikipedia entry

¶

¶ The Wikipedia entry on “Ringing Rocks” may be the most comprehensive summary on the subject at present, but at least 2 important citations are inaccessible to the general public, necessitating this Wikipedia section, rather than relying directly on source material. Additionally, several statements in the Wikipedia article have no specific citations, which possibly express opinions of the author.

¶ In Fig. 2 the ringing boulder fields in Bucks County, Ringing Rocks County Park and Stony Garden, are revealed to have formed along narrow surface exposures of the basal olivine unit, which is 10–15 ft (3.0–4.6 m) thick (McCray, 1997 unpublished Master’s thesis). The basal olivine unit is the narrow basal unit of the much-broader exposures of the overall diabase sills. The Wiki article states that the basal olivine unit is harder, denser and more resistant to weathering than diabase that crystallized higher up in the sill. “The basal olivine unit is similar to the one found in the Palisades Sill in New Jersey and New York. The olivine diabase unit is significantly harder, denser, and more resistant to weathering than the upper portions of the diabase sill.” This statement implies without explicitly stating that the boulders formed from basal olivine units have retained their nearly-pristine surfaces, with minimal weathering in the form of a thin weathering patina, whereas the boulders from the upper unit have either disintegrated entirely or have developed thick weathering rinds and significant rounding from repeated exfoliation episodes. The statement and implication of greater resistance to chemical weathering of the basal unit compared to the overlying diabase unit, however, is contrary to the Goldich dissolution series, which establishes that olivine and pyroxene have greater weathering potential than felsic minerals, namely feldspar, muscovite and quartz. When olivine and pyroxene come into contact with water, they undergo a metamorphic transformation, known as serpentinization, creating serpentinite silicates (Holm et al., 2014). Additionally, free oxygen oxidizes ferrous iron (Fe2+) to ferric iron (Fe3+) in ferrous silicates, forming iron oxides like hematite (Fe₂O₃) or goethite (FeO(OH).

¶ The Wiki article attributes the ringing quality of boulders to internal “loading stress” formed by compression at a depth of 2-3 km during igneous cooling and that the slow weathering rate of the boulders keeps the stresses from dissipating (by some unspecified mechanism). In the 1960s, an unnamed and unreferenced Rutgers University professor compared sawn slabs of “live” (ringing)boulders to slabs of “dead” (non-ringing) boulders from the same boulder field. By means of strain gauges, he discovered that the live boulder slabs exhibited a distinctive expansion (relaxation) within 24 hours of being cut, whereas dead boulder slabs did not similarly expand. Intrusive igneous diabase formed kilometers underground was indeed exposed to hydrostatic head pressure of the overlying rock units, but so was all other intrusive and plutonic rock that doesn’t ring, so why should diabase boulders fractured from bedrock at the LGM be different in that regard from diabase boulders fractured from bedrock at any other time period? The strain gauge test indicates that only live boulders contain stress amenable to being relieved by sawing into slabs (and presumably breaking into pieces), which suggests that the stress imbuing the ringing attribute is a surficial property rather than a bulk rock property, since sawed and broken pieces should still retain their bulk stress. Surface stress, however, would be relieved by sawing or breakage, and surface stress acquired at catastrophic brecciation could explain why only diabase boulders brecciated at the LGM acquire the ringing property.

¶ In a super-high-pressure catastrophic event, the surface of a boulder can experience more stress than the bulk rock inside. When a shock wave in air encounters a solid object like an igneous boulder, there is a significant mismatch in acoustic impedance. Due to this mismatch, most of the shock wave’s energy will reflect off the surface of the boulder, which will stress the surface compared to the interior due to the rapid compression followed by tension as the shock wave reflects. (GPT-4)

¶ Another peculiar feature of young boulder fields are deeply incised surface features, such as pits, striations and potholes, which are not found in diabase boulders outside the discrete boulder fields. The Wiki entry suggests “chemical weathering along joint surfaces when the rock was still in place and before the boulders were broken out by frost heaving,” followed by the mechanical removal of all chemically-softened material, but this begs the question of how chemically weathered material could have been so completely removed from deeply-incised surface features, when boulders in the woods just beyond the boulder field exhibit thick, cracked weathering rinds on their exterior surfaces. Alternatively, super-high-velocity ice or fluids capable of brecciating bedrock could be expected to scour pits and other surface features into the surfaces of brecciated boulders.

Figure 2: Ringing Rocks Park and Stony Gardens Park, in Bucks County, PA, showing derivation of diabase boulder fields from the basal olivine unit of the Newark Supergroup diabase sills

Image credit: Andrews66 / CC-BY-SA 3.0, ’Ringing Rocks’ Wikipedia page (unmodified)

………………..

3. Multiple primary impacts on the Laurentide ice sheet

¶

¶ In a seminal work on the YD impact theoryit was noticed that a small minority of Carolina bays had a major axis orientation that pointed much further north than the bulk of the bays (Firestone, West and Warwick-Smith, 2006). Taking the Coriolis effect into consideration, the majority of the major axes of Carolina bays converge toward the Great Lakes Region, while a small minority converge much further north, over Hudson Bay. This suggests at least 2 primary strikes or clusters of primary strikes on the Laurentide ice sheet—one on or over Hudson Bay and one on or over the Great Lakes region. The Taurid meteor stream has been hypothesized as the likely origin of the YD bolide, from the breakup of a large Kuiper belt object (Wolbach, 2018), and as such, multiple impacts might be expected.

¶ Hudson Bay is significantly more distant from anywhere in the contiguous United States than the Great Lakes Region, such that the speed of ballistic ice-sheet fragments over East-central Pennsylvania would have been significantly greater than those coming from the Great Lakes Region. And since kinetic energy is the squared function of velocity, the specific kinetic energy of secondary ice fragment impacts in Eastern Pennsylvania from Hudson Bay would have been several times greater than those from the Great Lakes Region. Indeed, perhaps only secondary impacts originating from the Hudson Bay Region with high specific kinetic energy were capable of forming impact boulder fields, at least in hard, tough diabase target rock.

¶ From Fig. 3, the trajectories in red that originated from Hudson Bay Region and formed Carolina Bays in the Delmarva Peninsula passed over Eastern Pennsylvania, such that any that fell short might be responsible for East-Central Pennsylvania boulder fields.

Figure 3: YD impact hypothesis, predicting the origins of primary bolide impacts on the Laurentide ice sheet, 12,800 ya, from the orientations of Carolina bays. The ballistic trajectories of ice-sheet-fragment ejecta curtains are indicated in red and blue. Red trajectories point back to suggested primary impacts over Hudson bay, with one cluster of red trajectories passing over Eastern Pennsylvania. Secondary ice-sheet-fragment impacts from the Hudson Bay Region are suggested here to have possibly formed a cluster of ‘YD impact boulder fields’ in Eastern Pennsylvania.

From (Firestone, 2009)

………………..

4. Allochthonous blockfields

¶ The Ringing Rocks type boulder fields are substantially autochthonous blockfields that lie directly or mostly over the bedrock that they fractured out of. But the ¾ kilometer-long Blue Rocks boulder field composed of Tuscarora Quartzite extends down over Ordovician Martinsburg Shale, indicating downhill flow as an allochthonous blockfield. And the ≥ 5:1 length-to-width aspect ratio of Blue Rocks at Hawk Mountain Pennsylvania is another indication of a dynamic downhill flow.

Blue Rocks boulder field evidence (Potter and Moss, 1968):

¶ Blue Rocks (40°36′ N, 75°55′ W) is a half-mile-long blockfield on the south slope of Blue Mountain in Eastern Pennsylvania, composed of angular blocks of Silurian Tuscarora Quartzite. The blocks are derived from strongly jointed quartzite cliffs on Blue Mountain and have moved downslope over Ordovician Martinsburg Shale. (It seems more natural to call Blue Rocks a blockfield rather than a boulder field, since the largest rocks are tabular blocks 20 feet long.) The blocks do not appear to be sorted along the long axis of the blockfield, but exhibit a strong degree of vertical sorting, decreasing in size from top to bottom; thus, the tabular blocks presumably slid down over much finer material underneath which churned like the boulders in Hickory Run boulder field.

¶ In a nearby borrow pit, rubble deposits similar to those of Blue Rocks overly reddish-brown material, “similar to material that Peltier (1949, p. 66)) suggested was Illinoian in age”.

¶ “The open-block area called Blue Rocks is a small part of a much larger rubble deposit

forming an apron that mantles the south slope of Blue Mountain for more than a mile on

either side of the boulder area. The gradient of the deposit (…) becomes progressively

lower downslope, ranging from 15° to as low as 3° near the terminus of Blue Rocks.”

¶ “Because a stream now flows beneath the open-block area, stream action is the most logical

mechanism for the removal of the fines (…), if there ever were any in the

open-block area.”

¶ The open-block field exhibits a series of lobes, which appear tie into step-like ridges in the adjacent tree-covered areas, indicating that the downhill flow was much broader than the open-block area.

¶ The heavily weathered rocks do not appear to exhibit deeply-incised surface features seen at Ringing Rocks type boulder fields or at Hickory Run boulder field. And the heavy weathering of block surfaces could indicate a greater exposure age than the LGM.

Blue Rocks critique:

¶ Due to the apparent absence of deeply-incised surface features, and the broad width of the brecciated rock, “for more than a mile on either side of the boulder area”, Blue Rocks may not be the result of a secondary impact. Additionally, no rock scale was noticed in the blockfield. But the local talus slopes and steep terrain could have been susceptible to landslides triggered by ground tremors caused by 1 or more nearby secondary impacts, possibly an impact on the north side of Blue Mountain that triggered a rockslide on the south side.

¶ So, direct evidence for a secondary impact, brecciating bedrock and triggering a rockslide for the formation of the allochthonous Blue Rocks blockfield is lacking.

Hickory Run boulder field, PA (Smith, 1953):

¶ “Bedrock in the vicinity of the boulder field is mapped as the Pocono Formation, of Mississippian age”.

¶ “The Wisconsin drift lies between 1 and 2 miles north of the boulder field (…), and the Illinoian drift extends many miles to the south (…).”

¶ “Numerous blocks in the boulder field are as much as 10 times larger than any observed in local exposures of till. (…) The boulder field fails to show the lithologic variety found in the local till.”

¶ “Despite minor irregularities, the overall appearance of the field is one of striking flatness, and the surface gradient is close to 1°.”

¶ “Abundance of conglomerate blocks on one side of the boulder field as compared with their virtual absence on the other side points to strictly local derivation and is incongruent with glacial deposition.”

¶ “Boulders of the same lithology show essentially the same range in size and the same degree of weathering in the different parts of the boulder field and on the uncovered parts of the adjoining slopes; neither characteristic shows any systematic change in a cross-valley direction. It is therefore indicated that the boulders were all formed and moved to their present position in one limited interval of time, and much more rapidly than they could have been broken down into smaller fragments by continued weathering during transportation or for a long time after accumulation. In terms of present-day processes in the area, this represents a decidedly anomalous situation.”

¶ “The above data indicate that the accumulation of the boulders marks a limited interlude in the late geomorphic history of the area, a time characterized by conditions and processes notably different from those now prevalent.”

Hickory Run boulder field critique:

¶ A more recent observation completes the picture. “Based on visual interpretation, the boulders upslope (east) at Hickory Run are larger, angular, and less spherical; those downslope (west) appear to be smaller, smoother, and rounder (…). Roundness reveals the strongest spatial trend in the data, with boulders being more angular in the east and more rounded in the west, for the 25-boulder dataset” (Wedo, 2013).

¶ The progression from larger more blockier rocks upvalley to the east and smaller, smoother and rounder rocks to the west leaves little doubt that the boulders were ground down by tumbling, and the low 1° relief suggests that the boulder stream had considerable kinetic energy from either a higher elevation and/or from a catastrophic event.

¶ Deeply-incised surface features in Hickory Run boulders (Figs. 8–9) appear to link Hickory Run boulder field to the ringing diabase boulder fields, suggesting a common origin, with the difference being greater downhill flow in the larger boulder field.

¶ An “area B” blockfield (41.04966 -75.63923) (Sevon, 1987) just to the south southeast of the main boulder field and almost contiguous contains more pristine blocks up to 10 m long. If ground zero occurred on the hills just north-east of the main boulder field, then mapping a large ice fragment in a slanting trajectory onto rough terrain could readily cause multiple debris flows or rockslides, forming multiple discrete allochthonous boulder fields.

¶ There are 3 remote apparently autochthonous blockfields in Hickory Run State Park, apart from the main boulder field and area B blockfield, and because of the tabular shape of the blocks in the remote fields, we’ll use the term ‘blockfields’. Two of the remote blockfields have a west-northwest major axis orientation suggestive of a Great Lakes origin (Fig. 4). In general, clastic rock is more brittle than igneous rock, which may not have required the higher specific kinetic energy of a Hudson Bay origin impact to brecciate bedrock. A third blockfield at (41.03998 -75.60872) has a more east-west orientation, but superimposing the terrain view over the satellite view indicates that this third blockfield may be a boulder covered ledge on the side of an overlooking hill.

Figure 4: Two remote blockfields in Hickory Run State Park that appear to be autochthonous blockfields

……………….

5. Incised surface features on impact boulder field boulders

¶

¶ If secondary impacts traveling at several kilometers per second shattered target bedrock, ablative melting of ice-sheet fragments during ballistic reentry presumably created super-high-velocity fluids that could have abrasively scoured exposed rock surfaces, possibly forming the observed pits, striations and potholes in discrete boulder fields. Incised surface features formed after brecciation suggests a brief temporal delay from the main brecciating impact. Ablative erosion that broke small ice chunks from ice-sheet fragments would have experienced greater specific aerodynamic drag than the main ice-sheet fragment, slightly delayed their arrival, and ablative melting of these slightly-delayed ice chunks may have scoured pits and striation in the surfaces of impact brecciated boulders, with larger potholes possibly formed by baseball-sized ice impacts.

¶ Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA, Ringing Rocks Park in Upper Black Eddy, PA and Hickory Run boulder field all appear to exhibit pitting, striations and potholes, and Hickory Run appears to exhibit broader surface erosion. Striations are defined here as sunken relief in the form of grooves that are not related to internal faults or fractures. Striations may be streams of super-high-velocity droplets ablated from an ice-sheet chunk that scoured out closely overlapping pits to form more-or-less continuous striations. And straight lines of super-high-velocity droplets could have mapped onto 3-dimensional boulder surfaces as curved lines. Potholes are defined here as deep broad pits with generally flat bottoms that are often accompanied by a groove that resembles a pot or pan handle. The large relative volume of material excavated from large potholes compared to ubiquitous pits would seem to indicate impact by super-high-velocity ice chunks, with handles formed by streams of trailing droplets ablated from the super-high-velocity ice chunks.

¶ In Europe, ‘cup marks’ and ‘ring marks’ on boulders and bedrock exposures are generally understood to be petroglyphs. Indeed, cup marks are frequently circumscribed by concentric rings that are very evidently man made, although the central cup marks or potholes could be natural, particularly when cup marks are accompanied by handles.

Ringing Rocks Park, Upper Black Eddy, PA:

¶ A large proportion of the diabase boulders at Ringing Rocks exhibit surfaces with a low relief of randomly-spaced pits that resemble a form of rusticated architectural masonry. Surface features are most prominent when viewed by a point source of light shining obliquely over the surface of a boulder, such as sunlight playing obliquely on the sides of boulders, creating high contrast between reflected sunlight and shadow. Here are examples of surface pitting at Ringing Rocks IMAGE.

¶ Fig. 2 indicates some movement of part of the Ringing Rocks boulder field beyond the basal olivine unit, making Ringing Rocks an intermediate type boulder field between autochthonous and allochthonous. While tumbling can fracture boulders, creating new sharp edges and corners, its chief effect is to round corners and edges and smooth surfaces by grinding abrasion, progressively lowering surface relief. One might suggest that tumbling could ‘rustify’ boulders, creating percussion marks from boulders knocking into one another, but the evidence that some surfaces are heavily pitted while other surfaces on the very same boulder are entirely devoid of pits eliminates this possibility. Psilovikos and Van Houten (1982) noted that the presumed ‘solution features’ at Ringing Rocks, which they described as “shallow pits” and “larger pits with circular or elongate shapes” are found on “horizontal or gently dipping surfaces”, which indicates surface features largely formed after any boulder movement. They suggest that, “Pitting on the bare joint surfaces has resulted from effective solution by rain in the absence of forest shelter and a mantle of soil. In contrast, exfoliation predominated in the surrounding wooded residual boulder field.” Under that scenario, we are asked to believe that the absence of tree cover alone can result in solution pits centimeters deep, despite the contrary evidence that overall the boulders exhibit negligible weathering in the form of a thin patina, compared to the thick cracked weathering rinds of the diabase boulders in the woods beyond. The thickness of the weathering patina can be gauged on recently fractured surfaces, or can be measured by scratching off the patina with a sharp implement.

Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA:

¶ The boulders of the autochthonous Ringing Hills boulder field are more pristine than at Ringing Rocks, since Ringing Hills experienced little movement to round corners by tumbling. Indeed, several of the largest boulders at the edge of the field could be fitted back together like a 3-dimensional puzzle by mating their fractured surfaces.

¶ For some reason, many fewer boulder surfaces at Ringing Hills are uniformly mottled with pits like those at Ringing Rocks, but potholes appear in greater abundance. Ringing Hills is the only diabase boulder field photographed for this study (Figs. 5–7, 25 and 26), and despite the relatively pristine surface features at Ringing Hills, the scoured relief is not well defined, since the boulder field was photographed on an overcast day without flash.

Hickory Run State Park:

¶ In general, incised surface features at Hickory Run boulder field are less well defined than on diabase boulder fields, perhaps partly due to faster weathering of the clastic rock and partly due a degree of continuing boulder movement after scouring. But a greater susceptibility to weathering may be accompanied by a greater susceptibility to erosive scouring at the outset, explaining why some Hickory Run boulders tend to exhibit deeper scouring than diabase boulders. Note the particularly-deep pits in Fig. 8 and the deep overall scouring in Figs. 9 and 27. The clastic sand grains and pebbles in clastic sandstone and conglomerate may provide more leverage for scouring fluids than the interlocked mineral grains of crystalline rock.

¶ The conical shape of the surface feature in Fig. 10 appears to be a percussion mark,

perhaps from a boulder slamming down from a great height after having been kicked up in the air at brecciation. This is additional evidence for a catastrophic origin of the boulder field.

Figure 5: Diabase boulder with pits and striations

From Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA

Figure 6: Diabase boulder with parallel striations

From Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA

Figure 7: Diabase boulder with deep potholes with handles

From Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA

Figure 8: Sandstone boulder with pits

From Hickory Run Boulder Field

Figure 9: Deep pitting on sandstone boulder

From Hickory Run Boulder Field

Figure 10: Sandstone boulder with conical percussion mark

From Hickory Run Boulder Field

Figure 11: Pitting and striations in cairn boulder

From Inverness Scotland

Figure 12: Rock with granular surface erosion

From Val Camonica, Italy

Image credit: Luca Giarelli / CC-BY-SA

………………..

7. Magnetic spherules in Pleistocene tusk and bone and in Clovis chert flakes

¶

¶ Firestone et al. (2006) discovered magnetic spherules embedded in Clovis chert flakes, with particle tracks caused by high-velocity spherule impacts. Similarly, magnetic spherules with entrance wounds were found in older Pleistocene tusks and bones (Fig. 21), circa 33 ka. Impact embedded magnetic spherules long before the Younger Dryas could be associated with the YD impact by evoking the progressive fragmentation of a large bolide in the inner solar system, as has been suggested for the origin of the YD impact bolide, with its remnants in the form of the Taurid meteor stream (Wolbach, 2018. This early evidence of high-velocity ground-level magnetic has not been followed up in more recent research papers on the YDIH, possibly due to the lack of a plausible origin story for high-velocity magnetic spherules at ground level.

¶ Birdshot fired from a shotgun is only good for 30 meters or so, and magnetic microspherules are orders of magnitude less massive than birdshot, such that even microspherules traveling at interplanetary speed would quickly burn up or slow down to terminal velocity in our thick atmosphere in an effect we’ll call ‘the last decameter problem’, which raises the question of what maintained the velocity of magnetic microspherules or reaccelerated them (in the last decameter) to speeds sufficient to penetrate bone, tusk and chert.

¶ Super-high-velocity spherules splintering off of a bolide of sufficient mass to maintain super-high-velocity speed at ground level is not a plausible origin, if the microspherules would have had to splintered off in the last decameter of a sufficiently-large bolide to have obliterated the mastodon or Clovis site with chert flakes with its impact crater. Because the penetrating microspherules were notably ‘magnetic’ (attracted to a magnet), it may be tempting to suggest some form of magnetic acceleration, but the broad area, covering most of the continental United States (Firestone et al., 2006), would appear to preclude a magnetic effect, since the magnetic field of a magnetic dipole (rapidly) falls off as an inverse cube function, and besides electromagnetism travels at the speed of light. But an atmospheric shock wave from the airburst of a not-too-distant bolide might locally accelerate microspherules in free fall, eliminating the last decameter problem. Thus, only microspherules raining down from the Taurid meteor stream that were fortuitously within a decameter or so of the target at the instant that an airburst shock wave passed by would have attained a sufficient velocity kick to penetrate bone, tusk, and chert.

Figure 21: A Siberian mammoth tusk, showing craters from 7 magnetic particles, with arrows marking the direction of travel.

From Firestone et al. (2006).

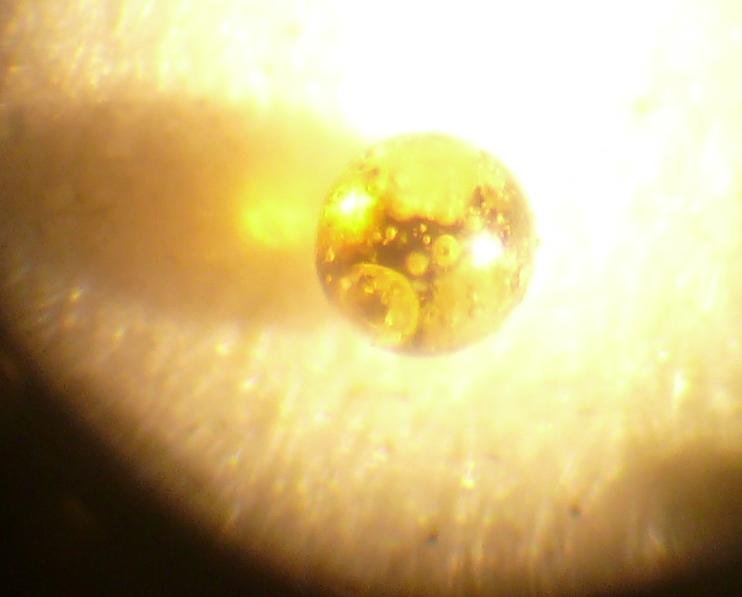

Figure 22: Magnetic glass spherule from Pennsylvania

………………..

8. Discussion

¶

¶ Inhomogeneity is the rule in the universe, which is well exemplified by the wide disparity in the composition of minor solar system bodies, and catastrophic mechanisms are better positioned to explain inhomogeneity than gradualistic ones. However, ad hoc impact hypotheses for the formation of Earth’s Moon, Venus’ retrograde rotation and Uranus’ extreme obliquity are among the most uninspired catastrophic mechanisms, and YDIH might be worthy of similar denigration were it not for the bright line onset for the Younger Dryas, coinciding with the megafaunal extinction in the Western Hemisphere. Instead, YDIH offers the potential to unify these 2 dramatic events, along with numerous lesser phenomena, such as spherule concentrations, platinum spikes and nanodiamonds found in the black mat and potentially surface features such as Carolina bays and discrete boulder fields attributed to the LGM. So a catastrophic YDIH is well positioned to explain the observed inhomogeneity at the YD boundary and to unify the disparate phenomena into a predictive falsifiable theory.

¶ Unification of phenomena is a small step in grounding the YDIH. Carolina bay formation by secondary impacts begs the question of the effects of secondary impacts that fell short of the coastal regions, but if discrete boulder fields can be positively assigned a catastrophic origin, then the case for a catastrophic origin for Carolina bays may also be strengthened. Thus, discrete boulder fields potentially provide corroborating evidence for Carolina bays and vice versa, the way scoured surface features may provide corroborating evidence for rock scale. And while Carolina bays apparently lack rocks necessary to retain the effects of scouring and splattering, the white sand in bay rims does appear to be abnormally bleached (Firestone et al., 2006).

¶ Most events leave identifiable ‘witness marks’, since it is impossible to completely rehomogenize the universe. In this regard, rock grit scoured from one boulder surface and splattered onto other boulder surfaces should persist to some degree to the present day, particularly considering the catastrophic heat and shock wave pressure that promoted mechanical and chemical bonding. If exceedingly ephemeral trace fossils and soft bodied fauna from hundreds of millions of years ago exist in the fossil record, then baked on oxides and silicates 10,000 times younger should still persist as well.

Figure 23: Diabase block with sharp corners and orange weathering rind

From Calvary Cemetery, Montgomery County, PA

Figure 24: Diabase block with sharp corners and orange weathering rind

From West Conshohocken, PA

Figure 25: Diabase boulder with deep potholes

From Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA

Figure 26: Diabase boulder with deep crossed striations

From Ringing Hills Park, near Pottstown, PA

Figure 27: Sandstone boulder hollowed out by scouring

From Hickory Run Boulder Field

Figure 28: Weathering rinds with shrinkage cracks on diabase boulders in woods surrounding the Ringing Rocks boulder field

From Fackenthal (1919)

………………..

References

¶

Butler, Barbara (1983). Petrology and geochemistry of the Ringing Rocks pluton Jefferson County Montana (B.A. thesis). Missoula: University of Montana

Boelhouwers, Jan, (2004), New Perspectives on Autochthonous Blockfield Development, April 2004 Polar Geography 28(2):133-146

Firestone, Richard; West, Allen; Warwick-Smith, Simon, (2006), The Cycle of Cosmic Catastrophes: Flood, Fire and Famine in the History of Civilization, Bear and Company

Firestone, Richard B., Analysis of the Younger Dryas Impact Layer, (2007), Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03q2r98x

Firestone, R.B.; West, A.; Kennett, J.P. et al., (2007), Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling, PNAS October 9, 2007, vol. 104, no. 41

Firestone, Richard B., (2009), The Case for the Younger Dryas Extraterrestrial Impact Event: Mammoth, Megafauna, and Clovis Extinction, 12,900 Years Ago, Journal of Cosmology, 2009, Vol 2, pages 256-285, Cosmology, October 27, 2009

Fackenthal, B.F. (1919). “The Ringing Rocks of Bridgeton Township”. A Collection of Papers Read Before the Bucks County Historical Society. Vol. 5. Bucks County Historical Society. pp. 212–221

Holm, N. G.; Oze, C.; Mousis, O.; Waite, J. H.; Guilbert-Lepoutre, A., (2014), Astrobiology. 2015 Jul 1; 15(7): 587–600

Husch, Jonathan M., (1992), Geochemistry and petrogenesis of the Early Jurassic diabase from the central Newark basin of New Jersey and Pennsylvania, DOI:10.1130/SPE268-P169

McCray, S.S. (1997). Petrogenesis of the Coffman Hill diabase sheet, Easton Pennsylvania (unpublished B.S. thesis). Easton: Lafayette College

Moore, Christopher R. et al., (2024), Platinum, shock-fractured quartz, microspherules, and meltglass widely distributed in Eastern USA at the Younger Dryas onset (12.8 ka), Airbursts and Cratering Impacts, 2024 Volume 2 Pages: 1–31

Petaev, Michail I.; Huang, Shichun; Jacobsen, Stein B.; Zindler, Alan, (2013), LARGE PLATINUM ANOMALY IN THE GISP2 ICE CORE: EVIDENCE FOR A CATACLYSM AT THE BØLLING-ALLERØD/YOUNGER DRYAS BOUNDARY?, 44th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (2013)

Potter, Noel Jr.; Moss, John H., (1968), Origin of the Blue Rocks Block Field and Adjacent Deposits, Berks County, Pennsylvania, 1968, Geological Society of America Bulletin

Psilovikos, A.; Van Houten, F. B.; (1982) Ringing Rocks Barren Block Field, East-Central Pennsylvania, Sedimentary Geology, 32 (1982) 233–243 233

Sevon, W. D., (1987), The Hickory Run boulder field, a periglacial relict, Carbon County, Pennsylvania, Geological Society of America Centennial Field Guide—Northeastern Section, 1987

Smith, H.T.U., 1953, The Hickory Run boulder field, Carbon County, Pennsyl

vania American Journal of Science, v. 251, p. 625-642

Wolbach, Wendy S. et al, (2018), Extraordinary Biomass-Burning Episode and Impact Winter Triggered by the Younger Dryas Cosmic Impact ~12,800 Years Ago. 1. Ice Cores and Glaciers, The Journal of Geology, Volume 126, Number 2, March 2018

I am interested in your position on the Nastapoka Arc as impact site. I have compiled an article on the same subject from material on the Web. If you are interested I could E-mail it to you.

I’ve been trying to figure out whether I have been finding meteorites or terrestrial iron when I stumbled across this page. I have the exact same rock scale and white cement covered iron in southern Indiana. I would love to send you some pictures. They look exactly like the ones in your pictures. I also have very large boulders with wear lines like you have shown.